Although we often hear about polygamy being practiced in the Utah Territory, the fact that the practice started in Nauvoo, Illinois, is not always publicized as well. It is estimated that Joseph Smith had more than forty wives, some of whom were already married to someone else and married him without the knowledge or consent of their husbands. Personal journals, diaries, and memoirs of early Mormon leaders narrate tales of Joseph Smith encouraging and sometimes commanding his Apostles to take plural wives, informing them that failure to do so would cause them to lose their Apostleship and be damned, and telling them to take young wives they could raise children by.

When Brigham Young led the 1848 company of pioneers to Salt Lake, he had 39 wives, 18 of whom are believed to have accompanied him on the trip. Heber C. Kimball, who served as first counselor to Brigham Young, had 37 wives at the time he travelled in the 1848 Heber C. Kimball Company, 14 of whom are believed to have accompanied him on the trip. Heber C. Kimball’s 31st wife was Ruth Amelia Reese, the sister of my fourth-great-grandmother, Catherine Reese Clawson. Ruth Amelia travelled separately in the Brigham Young Company. Howard Egan had three wives at the time he travelled in the 1848 Heber C. Kimball Company, one of whom was my fourth-great-grandmother, Catherine Reese Clawson, who had become his plural wife after she was widowed. Catherine travelled separately in the Brigham Young Company, while Howard’s first wife travelled with him.

One of the most disturbing aspects of this early practice of polygamy is that the wives in these plural marriages were often seen as trophies rather than as life partners. The polygamists were instructed by Joseph Smith that having multiple wives would ensure a special place in heaven for them. The marriages were often kept secret, and sometimes even the wives’ families were not informed of them. And when the men travelled west with some of their wives, many other wives were abandoned and left in Winter Quarters to be sent for later.

The Story of Catherine Reese Clawson

Catherine Reese was the fourth of twelve children raised by John Reese and Susannah Owen Reese. John and Susannah came from Montgomeryshire, Wales, and immigrated to New York City about 1800. After living in several New York State locations, they settled on a farm in Elk Creek, Pennsylvania. In 1823, they left their two oldest children in charge of the Pennsylvania farm and returned to New York City, planning to stay one year, but John became ill in New York and died in 1824. John and Susannah’s twelve children were: Rebecca, Susannah, Jonathan, Catherine, Mary, David, John, Edward, Enoch, Benjamin, Ruth Amelia, and Harriet.

Catherine Reese was born January 27, 1804, in New York City. She married Zephaniah Clawson on January 8, 1824, in Crawford County, Pennsylvania. Zephaniah was born May 13, 1798, in Crawford County, Pennsylvania, to John Clawson and Elizabeth Martin Clawson. Not much documentation can be found of Zephaniah’s early life, but this fun story of his school days appears in History of Crawford County, Pennsylvania (various authors, 1885, Warner Beers and Co., Chicago): “[School teacher] Joshua Pennel, in 1810, held a term. He tried to inculcate the habit among his pupils of thinking twice before speaking, and particularly with Zeph Clawson,·who often spoke rashly and unthinkingly. The master was standing one day with his back to the fire, when Zeph accosted him with ‘Well, master, I think—’ ‘That’s right, Zeph, now think again before you speak,’ interrupted Mr. Pennel. The lad kept silence till the teacher said, ‘Well Zeph, now speak.’ ‘Your coat is on fire,’ was the meek response. Zeph was allowed his natural way of speaking thereafter.”

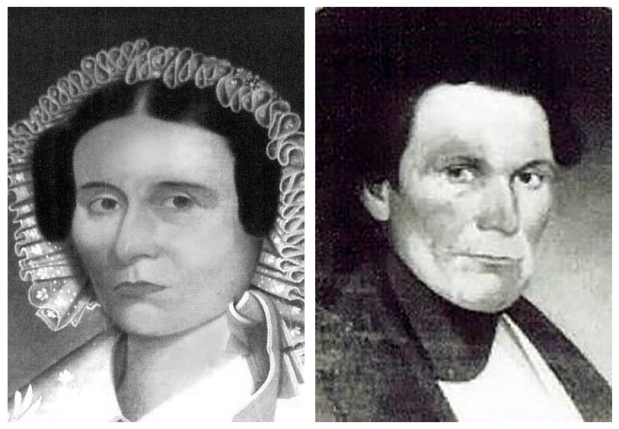

Catherine Reese Clawson and Zephaniah Clawson.

Catherine and Zephaniah had six children together. Two of their children, Susanna and Louisa, died as infants. Their four surviving children were: Hiram Bradley, John Reese, Helen Cordelia, and Harriet Cornelia. Zephaniah disappeared in September 1841 and is believed to have died in a steamboat accident on the Ohio River.

In 1844, Catherine Reese Clawson married Howard Egan as a plural wife. At the time of the marriage, Hyrum Smith (Joseph Smith’s older brother) told John D. Lee that this marriage “was a most holy one … in accordance with a revelation that the Prophet had recently received direct from God.”

When Catherine Reese Clawson crossed the plains in the 1848 Brigham Young company, she was listed as Catherine Clawson rather than as Catherine Egan, so this marriage was obviously not an important part of Howard Egan’s life. Catherine was travelling with her children, Hiram, Helen, and Harriet, and with her sister, Ruth Amelia. Ruth Amelia was married to Heber C. Kimball at the time (his 31st wife), but was listed in the company as Ruth A. Reese rather than as Ruth Kimball. Howard Egan and Heber C. Kimball were travelling separately in the Heber C. Kimball Company, Howard with his first wife, Tamson Parshley, and Heber with several of his other wives. Catherine’s oldest son, John Reese Clawson, had been serving with the Mormon Battalion in California and joined them in Salt Lake after they arrived.

This list shows Catherine Clawson, widow, travelling with her children, Hiram B., Ellen (Helen), and Harriet; and her sister, Ruth A. Reese. They are a part of the Anson Call Company of Fifty in the 1848 Brigham Young Company. They are travelling in two wagons, with six oxen and three cows. Catherine is the teamster for one wagon, and Hiram is the teamster for the other. There is no indication in this list that Catherine and Ruth are married to Howard Egan and Heber C. Kimball, respectively, or that Howard and Heber are travelling in a different company with other wives.

In 1851, Howard Egan shot and killed Catherine Reese Clawson’s nephew, James Madison Monroe. Catherine divorced Howard in 1852. This story will be related later.

On June 10, 1855, Catherine Reese Clawson became another in the long list of plural wives of Brigham Young, but she appears to still have been known as Catherine Clawson, as that is the name she used in the 1856 Utah Statehood Census Index. I have not yet been able to find her in the 1860 U.S. Census, so I don’t know what name she may have used on the census that year.

Catherine Reese Clawson died on November 7, 1860, in Salt Lake City. In the Utah Death Register, she is listed only by the name Clawson, with no first name, no list of close family, no birth date and place, no death date and place, and her burial location listed as “Young Lot.” According to cemetery records, she is buried in a pauper’s grave next to her brother John in the Salt Lake City Cemetery, where they share a headstone at plot number B_4_PAUPER_756. The headstone gives her name as Catherine Reese Clawson.

Catherine Reese Clawson and Colonel John Reese share a headstone in the Salt Lake City Cemetery. This headstone was placed there in 2015 by the descendants of their brother Enoch Reese.

The Siblings of Catherine Reese Clawson

This is the story of Catherine Reese Clawson and her marriage to Howard Egan, but it cannot be complete without also listing her siblings who were also participants in plural marriages. According to the journals of Catherine’s brother Enoch Reece, four of the Reese sisters joined the Mormon church in 1841. The only other siblings whom I could find records of joining the church are one sister: Ruth Amelia; and two brothers: Enoch, who joined the church and moved to the Utah Territory, and John, who joined the church after moving to Utah. Both brothers had multiple wives after their move to Utah. Ruth Amelia became a plural wife while still in Nauvoo. I assume that the other two sisters mentioned by Enoch Reese as having joined the church in 1841 might be Rebecca, whose son James Madison Monroe later moved to Utah and was shot and killed by Catherine Reese’s second husband, Howard Egan; and Susannah, whose son David H. Kinsey died in Salt Lake City and son Stephen A. Kinsey died in Genoa, Nevada, which had been settled by John and Enoch Reese.

Ruth Amelia Reese Kimball

Ruth Amelia Reese was the eleventh of twelve children raised by John Reese and Susannah Owen Reese. She was born May 10, 1817, in Beaver Township, Crawford County, Pennsylvania. She was six years old when her father died. According to her brother Enoch Reese’s journal, after their father’s death, all the siblings except Enoch and Catherine moved from the family farm in Crawford County, Pennsylvania, to New York, where their mother lived, so Ruth would have moved to New York at that time.

Ruth joined the Mormon church and moved to Nauvoo, Illinois, where she became the 31st wife of Heber Chase Kimball. As stated above, Ruth travelled to Salt Lake City in the Brigham Young Company of 1848 under her maiden name, while her husband was travelling with several other wives in the Heber C. Kimball Company. At the time they left Winter Quarters, Heber C. Kimball was second only to Brigham Young in the number of wives they had. Young had 39; Kimball had 37.

One question that came to mind was whether Ruth’s travelling under her maiden name might be an indication that her marriage to Heber C. Kimball was not considered as important as marriages to some of his other wives. My research into the life of Heber C. Kimball showed that he had married several widows (particularly widows of Hyrum and Joseph Smith) who lived their lives separately from him and his other wives, but that would not be the case with Ruth, who had never been previously married. Then I started looking at all the wives who travelled in the 1848 companies to see how they were listed on the rolls of the companies.

Of Heber’s thirty-seven wives, fourteen of them migrated to Salt Lake in 1848. One wife, Ellen Sanders Kimball, was already in Salt Lake, having travelled with Heber in the 1847 Brigham Young Company, one of only three women in that company. The remaining twenty-two wives remained in Winter Quarters to make the journey at a later date. My main source for information about their travels was the Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel database at history.lds.org, which might not accurately show the names they were using during the journey. I was lucky to find a roster showing that Ruth A. Reese was travelling in the Brigham Young Company with her sister Catherine Reese Clawson, because the Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel database mistakenly shows her in the Heber C. Kimball Company under the last name of Kimball. I have not been able to find this kind of documentation for Heber’s other wives, and not everything in the Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel database is thoroughly documented, so I cannot be sure of the accuracy of a lot of it, but I am sharing my findings here.

Eight wives travelled in the Heber C. Kimball Company under the name Kimball: Vilate Murray Kimball, Sarah Peak Noon Kimball, Sarah Ann Whitney Kimball (who was a widow of Joseph Smith, but did not live separately from Heber C. Kimball’s family as some other widows did), Amanda Trimble Gheen Kimball, Harriet (born Helga, which had been Americanized to Harriet) Sanders Kimball, Christeen Golden Kimball, Laura Pitkin Kimball, and Mary Ann Shefflin Kimball. As stated earlier, Ruth Amelia Reese Kimball travelled with her sister in the Brigham Young Company under the name Reese. Charlotte Chase Kimball (who would divorce Heber the following year) travelled with her parents in the Brigham Young Company under the name Kimball. Ann Alice Gheen Kimball travelled in the Willard Richards Company under the name Kimball. Mary Fielding Smith Kimball (widow of Hyrum Smith) travelled in the Heber C. Kimball Company under the name Smith. Lucy Walker Smith Kimball (widow of Joseph Smith) travelled in the Heber C. Kimball Company under the name Smith. Presendia Lathrop Huntington Buell Smith Kimball (widow of Joseph Smith, although she was also married to Norman Oliver Buell, who left the church because of Presendia’s involvement in polygamy and remained in Missouri for the rest of his life) travelled in the Heber C. Kimball Company under the name Buell.

It is unclear whether Frances Jessie Swan Kimball, who travelled in the Heber C. Company under the name Swan, was married to Heber before or after their journey to Salt Lake. She later left the church because of her disagreement with the principle of polygamy, and lived the rest of her life in California with her new husband, George C. Clark.

Although some of Heber C. Kimball’s marriages ended in divorce, most personal histories written by members of his family indicate that he treated his wives well. They lived in several houses, but appear to have lived as one extremely large family unit. It doesn’t appear that Ruth Amelia Reese Kimball was ever mistreated in any way by her husband. They had three children together, but none of them lived long enough to provide her with any grandchildren. Their daughter Susannah R. Kimball, died on the same day she was born, July 10, 1851. Their younger son, Enoch Heber Kimball, born September 2, 1855, died on August 20, 1877, when he accidentally shot himself while retrieving his shotgun from the wagon after returning from a hunting expedition with relatives in Meadowville, Rich County, Utah. Their older son, Jacob Reese Kimball, born April 15, 1853, died after a prolonged illness on May 30, 1875, in Salt Lake City. Perhaps inspired by the time she spent treating Jacob before his death, Ruth spent the rest of her life dedicated to tending to the ill and afflicted until about 1890, when her active life was curtailed by blindness. She was also said to have been an excellent tailoress, and Heber was proud of all his clothes that she made for him.

Ruth Amelia Reese Kimball died of general debility and old age on November 26, 1902, in the home of her nephew, John Heber Reese, in Salt Lake City. She is buried in the Salt Lake City Cemetery at plot number G_14_10_3EN2. Many other Reese relatives are buried nearby. Her children are all buried in the Kimball-Whitney Cemetery in Salt Lake City, along with their father and many of his other wives and children.

Colonel John Reese

John Reese was the seventh of twelve children raised by John Reese and Susannah Owen Reese. He was born October 15, 1808, in Whitestown, Oneida County, New York. After his father died in 1824, he moved with most of his siblings from the family farm in Pennsylvania back to New York, where his mother was living.

John Reese married Catherine Miles about 1832 or 1833 in New York City. They had three children that I know of, all born in New York City: Mary Miles Reese, born October 15, 1838; Miles Reese, born about 1842; and William McIntosh Reese, born August 13, 1847. Although I haven’t seen any documentation of John’s military service, it appears that he served in the New York Militia and was known for the rest of his life as Colonel John Reese.

In 1849, John’s brother Enoch, who had joined the Mormon church in 1841 and moved to Nauvoo in 1844, was preparing to travel to Salt Lake City with his family in the Allen Taylor Company. John decided to leave his wife and children in New York to travel with his brother and his family, bringing a large load of goods in order to become merchants in the Utah Territory. After arriving in Salt Lake, John went back almost immediately for more goods, while his brother opened a store named J. & E. Reese.

John returned to Salt Lake in 1850 with more goods, and the brothers ran their business there during that year. In Spring 1851, John loaded up thirteen wagons with eggs, bacon, flour, and seeds, and travelled to Carson Valley, on the western edge of the Utah Territory. He was the first non-native to settle in the area, and he built a house known as Mormon Station (also known as Reese’s Station) that served as a boarding house and trading post. He cultivated thirty acres to grow goods to sell to the miners heading to and from the California gold fields. After the house was completed, he sent for his wife and family who travelled by boat to San Francisco, where he met them to escort them to their new home. This settlement later became the town of Genoa, Nevada. His brother Enoch joined him there for a couple of years, and together they are considered the founders of Genoa.

Around 1859, John sold his business interests in Genoa and moved back to Salt Lake City, where he married his second wife, Louisa M. Christian, who was sixteen years younger than he was; and his third wife, Caroline Emily Wilkie, who was thirty-nine years younger than he was. He had four children with Louisa M. Christian: Katherine Christian Reese, Sarah E. Reese, Louise Christian Reese, and Alfred Christian Reese. He had five children with Caroline Emily Wilkie: Samuel Wilkie Reese, Edward Wilkie Reese, Dollie Emilie Reese, Emilie Ann Reese, and Benjamin F.W. Reese.

John Reese’s first wife, Catherine Miles, divorced him February 27, 1875. All I have is a newspaper account announcing the divorce, so I have no details of the circumstances.

John Reese’s third wife, Caroline Emily Wilkie, married Albert Leith about 1878. I assume that she must have divorced John Reese prior to this, but I have not been able to find any documentation of it. There is a possibility that she just stopped being his wife in accordance with the Morrill Anti-Polygamy Act of 1862, but that is doubtful, since the act was never actively enforced. It has been said that President Abraham Lincoln gave Brigham Young permission to ignore the act in exchange for not becoming involved in the Civil War.

So when John Reese died on April 20, 1888, in Salt Lake City, he had only one wife. His funeral service was held at Saint Mark’s Cathedral, an Episcopal church, so he was probably no longer associated with the Mormon Church at the end of his life. He is buried in a pauper’s grave next to his sister Catherine Reese Clawson in the Salt Lake City Cemetery, where they share a headstone at plot number B_4_PAUPER_756. The headstone gives his name as Colonel John Reese.

Enoch Reese

Enoch Reese was the ninth of twelve children raised by John Reese and Susannah Owen Reese. He was born May 25, 1813, in Whitestown, Oneida County, New York. When his father died in 1824, he remained in Pennsylvania, living with his sister Catherine and her husband, Zephaniah Clawson. They soon moved to New York, where Enoch learned the trade of masonry, which he followed for many years.

Enoch married Delia D. Briggs on January 4, 1837, in Utica, New York. They had two sons, Edward Briggs Reese and Charles E. Reese, both of whom died in infancy. Delia died September 3, 1839, possibly from complications of the birth of their second son.

Upon returning to Buffalo, New York, in 1841, he was surprised to learn that four of his sisters had joined the Mormon church, but then he also decided to join. He presided over a Mormon branch in Buffalo for a while.

Enoch married Hannah Harvey on September 30, 1843, in Buffalo. They had six children together: Enoch Moroni Reese, David Reese (who died as an infant), James Henry Reese, Hannah Adelia Reese (who died as an infant), Susannah Lavina Reese (who died as a young girl), and Isaac Genoa Reese. They also had two adopted Native American daughters: Jane Reese and Ann Reese. They moved to Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1844, and migrated to Salt Lake in the 1849 Allen Taylor Company with their two oldest sons and Enoch’s brother John.

After arriving in Salt Lake, Enoch took three additional wives. He married Sarah Ellen McKinley on June 22, 1850, and they had two sons together: John Heber Reese and Enoch Leo Reese. He married Ann Eliza Dunlap (widow of Bradford White Elliott) on April 18, 1856, and they had three daughters together: Ruth Amelia Reese, Mary Ellen Reese, and Alice Reese (who died as an infant). He married Amy Jane Wightman on January 4, 1865, and they had four children together: Milton Alma Reese (who died as an infant), Charles Wightman Reese, Amy Estella Reese (who died as a young girl), and Joseph Wightman Reese. All of Enoch’s wives were younger than he was, but his last wife, Amy Jane Wightman, born October 26, 1844, was thirty-one years younger, even younger than Enoch’s oldest surviving son, Enoch Moroni Reese.

After migrating west, Enoch lived most of his life in Salt Lake City, but he did spend some time in Genoa, Nevada, working with his brother John at their business there. They are recognized by the state of Nevada as the founders of Genoa, although records seem to show that John arrived there without him and actually built the business himself. Also, the birth dates of Enoch’s children seem to indicate that he didn’t remain away from Salt Lake for long periods of time.

Enoch Reese died July 20, 1876, in Salt Lake City. He died intestate, and his probate proceedings weren’t finalized until 1894. The heirs listed in the final petition papers include one wife (Hannah Reese, who was named as his widow) and his eight surviving children (Enoch Moroni Reese, Isaac Genoa Reese, John Heber Reese, Enoch Leo Reese, Ruth Amelia Reese, Mary Ellen Reese, Charles Wightman Reese, and Joseph Wightman Reese). One wife (Anna Eliza Dunlap) and two of his children (James Henry Reese and Amy Estella Reese) died between the time of his death and the time his estate was settled. His other two surviving wives (Sarah Ellen McKinley and Amy Jane Wightman) are not mentioned as heirs. His estate was reopened in 1949, but only to clear up a cloud caused by an ambiguous property description on a title of land that Enoch had sold prior to his death.

Enoch Reese is buried in the Salt Lake City Cemetery, at plot number B_13_2_1W, next to his wife, Hannah Harvey Reese, buried at plot number B_13_2_2W. Wives Sarah Ellen McKinley Reese and Ann Eliza Dunlap Reese are buried in different sections of the Salt Lake City Cemetery. Wife Amy Jane Wightman Reese is buried in the Payson City Cemetery in Payson, Utah County, Utah, along with two of her children.

The Story of Howard Egan

Now we get to the meat of the story, the marriage of Catherine Reese Clawson to Howard Egan, who had taken her as a plural wife after she was widowed. It is hard to tell if it was a marriage in anything more than name. There is no evidence of them having lived together; they had no children together; and they migrated to Salt Lake City in separate companies, he with his first wife and she with her children and her sister.

Howard Egan was the sixth of ten children born to Thomas Howard Egan and Ann Meath Egan. Thomas Howard and Ann were from County Offaly, Ireland, where all their children were born: Eliza Egan, Mary Egan, Catherine Egan, Bernard “Barney” Egan, John Egan, Howard Egan, Ann Egan, Richard Egan, and twins Eliza and Margaret “Gretta” Egan.

Howard Egan was born June 15, 1815, in Tullamore, County Offaly, Ireland. He was not quite eight years old when his mother died on February 15, 1823. There is no record showing a cause of death, but as she had given birth to twins two weeks prior, her death may have been caused by complications of childbirth. Two years later, his father took all the family (except for Gretta, one of the twins, who was left with an aunt in Ireland) to Montreal, Quebec, Canada. This was the second phase of the Irish migration to Canada financed by the British government to transport poor families from Ireland, which was in the middle of a depression at the time, to Canada. They can be seen on the passenger list of the steamship Chambly, travelling from Quebec City to Montreal on June 7, 1825, listed as Thomas Howard Agan and seven others and two children under twelve. (Actually, four of the children, including Howard, were under twelve, but you can’t fault a poor nineteenth-century immigrant for not having the mathematical abilities to calculate all his children’s ages.)

Three of the children, Eliza, Barney, and Ann, died within a year of their arrival, and Thomas Howard Egan died August 5, 1828, leaving six orphans. After the death of his father, Howard Egan is believed to have stayed with his sister Catherine and her husband, John Ransom, until he was old enough to procure a job as a seaman, working on boats on the rivers of Canada. Around 1836, he moved to Salem, Massachusetts, where he learned the trade of rope making, and he continued in that profession for the next ten years.

Howard Egan married Tamson Parshley December 1, 1839, in Salem, Massachusetts. He was twenty-four years old; she was fifteen. Howard had learned prior to their courtship that Tamson was prejudiced against the Irish, so he changed the pronunciation of his last name to make it sound more French-Canadian, and he told her he was born in Montreal. It wasn’t until after his death that she learned he was born in Ireland. At the time she found out, she said, “I will never forgive him and he will have to pay for it in heaven,” but by the time she died she had forgiven him for lying to her.

Howard and Tamson had five sons: Howard Ransom Egan and Richard Erasatus Egan, born in Salem; Charles John Egan, born in Nauvoo and died as an infant; and Horace Adelbert Egan and Ira Ernest Egan, born in Salt Lake City.

Howard Egan became a United States citizen in 1841. He and Tamson joined the Mormon church in 1842 and moved to Nauvoo, Illinois, to gather with the other Mormons. While living there, Howard opened a rope-making factory and served as a Nauvoo policeman and sometimes as personal guard for both Joseph Smith and Brigham Young. He also served in the Nauvoo Legion. Some histories say that this is when he became known as Major Howard Egan, but he reached only the rank of Captain in the Nauvoo Legion at that time. It wasn’t until years later (1857–1858) in Utah, when the Nauvoo Legion was reactivated by Brigham Young to repel the United States Army forces commanded by Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston from reaching Salt Lake, that he was called into service with the rank of Major.

In 1844, Howard Egan married Catherin Reese Clawson in Nauvoo. She was a widow and eleven years older than he, and this marriage doesn’t seem to have carried the same importance as his other marriages, despite the fact that Joseph Smith’s brother Hyrum described the marriage as “a most holy one … in accordance with a revelation … direct from God.” Catherine appears to have continued using the last name of Clawson throughout the rest of her life. They had no children together and would divorce after eight years of marriage.

Also in 1844, Howard Egan was sent as a Mormon missionary to New Hampshire, but his mission also doubled as a volunteer effort on behalf of Joseph Smith’s Presidential campaign. In addition to being assigned the usual missionary duties, those being sent out that year were also instructed to “present before the people ‘General Smith’s Views of the Powers and Policy of the General Government,’ and seek diligently to get up electors who will go for him for the Presidency.”

Howard Egan married his third wife, Nancy Ann Redden, on January 23, 1846, in Nauvoo. They had two daughters together, Helen Jeanette Egan and Vilate L. Egan, both born in Winter Quarters, Nebraska. This marriage would last for only a short time. Although I can’t find a record of their divorce, Nancy can be seen in the 1850 census living under her maiden name with her two daughters in the household of Joseph Johnson, probably as a boarder. She married Alonzo Hazeltine Raleigh on May 5, 1856, in Salt Lake City, a marriage in which she was one of many plural wives. She had one son with him, George Redden Raleigh. It appears that she also left this marriage, because she can be seen in the 1860 and 1870 censuses under her maiden name with her children, and in the 1880 census under the name Egan living with her daughter Helen and her family. She died on April 3, 1892, in Salt Lake City. Her obituary and her headstone give her last name as Raleigh.

In March of 1846, Howard Egan and his wives and children moved from Nauvoo to Winter Quarters (now the Florence neighborhood of Omaha, Nebraska), along with most of the Mormon population of Nauvoo. He had already put in the foundation for a new house he was building for his family in Nauvoo and had to abandon it in order to make the move. Then, in September through October of 1846, Howard Egan went with John D. Lee on an assignment in which they travelled to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, then on to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and back to Winter Quarters in order bring back the pay of the members of the Mormon Battalion to distribute to their families.

In April 1847, Howard Egan left his three wives behind in Winter Quarters, two of them pregnant, in order to travel with the Brigham Young Vanguard Company, the first company of Mormons to travel to Salt Lake. He returned in October to find he had two new children. In June 1848, he again left Winter Quarters to travel to Salt Lake in the Heber C. Kimball company. He travelled with his first wife, Tamson Parshley, and their three children. His second wife, Catherine Reese Clawson, travelled separately in the Brigham Young Company, with her children and her sister. His third wife, Nancy Ann Redden, remained in Winter Quarters waiting for him to return to bring her to Salt Lake. He then returned to Winter Quarters, and in April 1849, he organized the Howard Egan Company, in which he travelled to Salt Lake with his third wife, Nancy Ann Redden, who was pregnant at the time, and their daughter.

Within months of arriving in Salt Lake, Howard Egan married his fourth wife, Mary Ann Tuttle. He and Mary Ann had one son together: Hyrum William Egan. Mary Ann divorced Howard sometime before 1854. On January 20, 1854, Mary became a plural wife of Titus Billings. She was thirty-seven years younger than he, and younger than all but one of his surviving children. She had three children with him who survived to adulthood, but Mary Ann and Titus divorced sometime before his death in 1866. Mary Ann cannot be found in the 1860 or 1870 censuses, but two of her children, Emily Billings and Hyrum William Egan, appear to be living with Titus Billings and his first wife in the 1860 census. On November 28, 1866, Mary Ann became the second wife of her sister Martha Ann Tuttle’s husband, Walter Elias Gardner. They had one son. She died December 10, 1910, in Bicknell, Wayne County, Utah. Although her last husband was Gardner, her headstone shows her with the last name of her second husband, Billings.

In November 1849, Howard Egan left for California, acting as a guide for gold seekers. His new wife, Mary Ann Tuttle, was pregnant at the time. During the next two years, he returned to California more than once, sometimes as a prospector as well as a guide. After returning from one of these trips in 1851, Howard discovered that in his absence his first wife, Tamson Parshley, had given birth to another man’s baby. The other man was James Madison Monroe, the nephew of Howard’s second wife, Catherine Reese Clawson. Howard immediately went looking for James Madison Monroe, and when he found him he shot and killed him. Catherine divorced Howard the following year.

During the next several years, Howard had many occupations, most of which kept him away from home most of the time. He was a trailblazer, and one route to California that he explored, known as Egan’s Trail, was later used by the Overland Mail and the Pony Express. He worked as a cattle drover, driving stock to California. He was a carrier for the Overland Mail and later acted as superintendent. He was a superintendent for the Pony Express, and although the Pony Express specifically wanted young men (around eighteen years old) as riders, Howard Egan was known to ride a route occasionally when circumstances deemed it necessary. While acting as superintendent for the Overland Mail, Howard purchased the Deep Creek ranch in western Utah, which became his family’s principal home as well as a station on the Overland Mail line, and later a station for the Pony Express.

The plaque on this portrait identifies Major Howard Egan as Pioneer–Frontiersman–Pony Express Rider.

After the completion of the telegraph lines and railroads from coast to coast, the Overland Mail and Pony Express were no longer needed. After a long active life, Howard settled down and worked as a store owner, Third Judicial District Court deputy clerk, and Salt Lake City policeman, an odd occupation for someone who is known to have killed for vengeance.

Howard also acted a special guard for Brigham Young, and after Young’s death Howard served as a special guard at his grave. A building was erected specifically so that Howard could look out over the grave at night without getting out of bed. On one cold winter night, Howard got his feet wet while guarding the grave, which resulted in an illness that took his life on March 16, 1878. He is buried in the Salt Lake City Cemetery next to his first wife (and at the time his only wife), Tamson Parshley.

The Murder of James Madison Monroe

The murder of James Madison Monroe is important not only because it was the cause of Howard’s divorce from Catherine Reese Clawson, but also because it set a precedent in Utah courts that allowed men to get away with murder for decades to come.

James Madison Monroe was the son of Catherine Reese Clawson’s sister, Rebecca Reese, and her husband, William C. Monroe. His parents were married about 1818 in Elk Creek, Erie County, Pennsylvania, where his mother had worked as a school teacher. Not much information can be found about James’s father. His mother can be seen as head of household in the 1840, 1850, and 1860 censuses, but there is no indication as to whether she was divorced or widowed. Since the city directories from Utica, New York, in the 1860s list her as Mrs. Rebecca Monroe, I am assuming that she was widowed. In addition to her son, James Madison Monroe, she also had two daughters, Henrietta Monroe and Cornelia Monroe Frintz. Rebecca died of pneumonia on February 25, 1873, in Green Township, Hamilton County, Ohio, and she is buried along with her two daughters in the Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati, Ohio.

James Madison Monroe was born January 9, 1823, in Elk Creek, Erie County, Pennsylvania. He was the second of the three children in the family. He joined the Mormon church in 1841 along with others in his family in Buffalo, New York. He soon moved to Nauvoo, Illinois, where he lived from 1842 to 1845. While in Nauvoo, he built a school house, and he worked as the personal tutor for the children of Joseph Smith. In his personal journals from his time in Nauvoo, he refers to Joseph Smith’s wife as Aunt Emma, but this seems to be a term of endearment rather than any indication that they were somehow related. He also makes references in his journals to Aunt Catherine and Aunt Ruth, who would be his Aunts Catherine Reese Clawson and Ruth Amelia Reese.

I could not find any record of his travelling to Utah, but I would assume that once he was there he worked at the store owned by his uncles, Enoch Reese and Colonel John Reese, especially since the wagon train he was in at the time of his death was known as the John Reese Freight Train. I haven’t found any documentation of his life in Salt Lake City, but some family historians say that he boarded at the home of Howard Egan and Tamson Parshley. This would seem to make sense, as his aunt Catherine Reese Clawson was one of Howard’s wives. It would also have set up a situation that could have led to his romantic liaison with Tamson Parshley while Howard Egan was out of town.

When Howard Egan returned from one of his expeditions to California in late 1851, he discovered that in his absence his wife had given birth to a son fathered by James Madison Monroe. Although the child was the son of James Madison Monroe, he was given the name William Moburn Egan, and throughout his life he was raised no differently any other child in the Egan household. Upon learning about this birth, Howard immediately set out to find James Madison Monroe, seeking revenge. James Madison Monroe had already left town, but was returning in the John Reese Freight Train, bringing goods for the stores owned by Enoch and John Reese.

William Woodward, one of the teamsters in the wagon train, described this incident in his journal: “About the twenty-fourth of September, as we were ‘rolling out’ of camp, a person rode in and conversed with Mr. Monroe. The man was a stranger to me. This was in the vicinity of Yellow Creek, and about seventy miles from the Valley. The next I saw of him, he came riding by saying, ‘Gentlemen, I have killed the seducer of my wife.’ He put his hand to his breast and said, ‘Vengeance is sweet to me.’ Our captain rode past and gave orders to stop. I went back to see what was the matter, and James Monroe lie dead. He was shot by Howard Egan, for seducing his wife.”

Howard Egan returned to Salt Lake City and turned himself in to authorities, and he was put on trial for the murder of James Madison Monroe.

Among the arguments put forth by the defense lawyer, George A. Smith, were the following: “Quoted by the learned prosecutor yesterday … the person killed should be, or must be, a reasonable creature. … It was admitted on the part of the prosecution, that James Monroe … had seduced Egan’s wife. … A reasonable creature will not commit such an outrage upon his fellow man. … In this territory it is a principle of mountain common law, that no man can seduce the wife of another without endangering his own life. … The principle, the only one that beats and throbs through the heart of the entire inhabitants of this Territory, is simply this: The man who seduces his neighbor’s wife must die, and her nearest relative must kill him! … If Howard Egan had not killed that man, he would have been damned by the community for ever. … If Howard Egan did kill James Monroe, it was in accordance with the established principles of justice known in these mountains. … This act of killing has been committed within the Territory of Utah, and is not therefore under the exclusive jurisdiction of the United States. … The jurisdiction of the United States extending to this case, does not exist.”

The presiding judge, Zerubbabel Snow, seemed to agree with the defense concerning “mountain common law.” Toward the end of his instructions to the jury, he said, “If you find the crime … was committed within that extent of country between this and the Missouri river, over which the United States have the sole and exclusive jurisdiction, your verdict must be guilty. If you do not find the crime to have been committed there, but in the Territory of Utah, the defendant, for that reason, is entitled to a verdict of not guilty.”

It took the jury fifteen minutes to reach a verdict of not guilty.

This case set a precedent in the judicial system of Utah that continued for a long time. Men who were accused of killing, or attempting to kill, the seducers of their wives or daughters were found not guilty by claiming the Egan defense.

As late as 1877, the Egan defense was used in an attempted murder trial, where William Hobbs was charged with attempting to kill Cornelius Joseph “Con” Sullivan, the alleged seducer of his daughter. Sarah Ann Hobbs, the daughter of William Hobbs, was engaged to be married to Con Sullivan, a local saloon keeper. Hobbs, suspecting “criminal intimacy” between Sarah and her fiancée, forbade his daughter to leave their home in West Jordan one Sunday night. She ignored his order and fled into the night with Con Sullivan. William Hobbs went to the Sullivan house, forcibly entered the house, destroyed the furniture therein, and threw Con’s belongings out into the street. When Hobbs discovered the following day that Sarah and Con had gone to Salt Lake, he took his pistol and went looking for them. He finally found them at the Eagle Emporium, where he drew his gun and fired a shot at Con. The shot missed, and Con and Sarah fled down First South Street with Hobbs in pursuit. Hobbs fired three additional shots, two of which struck Con, but neither wound was fatal.

William Hobbs was arraigned on a charge of assault to commit murder. The judge presiding over the case was Bishop Alexander Cruickshank Pyper. The prosecuting attorney was, ironically, Judge Zerubbabel Snow, who had presided over the Howard Egan case. The defense attorney was the city attorney for Salt Lake City, Joseph Lafayette Rawlins. The prosecution brought Sarah Ann Hobbs to the stand, who testified that her father was the man who shot Con Sullivan. Then the defense attorney had her testify that she and Con had been “criminally intimate” about a year previously and that on the night of the attack they had registered at the Townsend House Hotel. Surprisingly, Judge Snow, who was acting as prosecuting attorney, also testified for the defense, stating that Hobbs had asked him the night after the shooting if he could have Con arrested for running away with his daughter.

Judge Snow, in his statement for the prosecution, said that although homicide would have been justified in the heat of passion, there had been time for Hobbs to cool off before committing the act. Rawlins, in his statement for the defense, portrayed Hobbs as a “noble father,” defending the honor of his family. Bishop Pyper discharged the defendant, saying no assault had been committed. The following year, Con Sullivan and Sarah Hobbs were married. They moved to Chicago, and later settled in Custer County, Idaho, where they raised a large family together.

Conclusions

There are several disconcerting aspects to the practice of polygamy by the early Mormons. One of most troubling is the number of wives left in dire economic situations and children left with no male leader in the house while the husbands and fathers left for months and sometimes years at a time doing missionary and church work and exploring and trailblazing the western part of the country. Howard Egan seems to have been home only a few months at a time during most of his life. Although John Reese’s leaving his wife and children in New York for years while he settled the area of Genoa, Nevada, happened prior to him becoming a polygamist, that action gives an indication of what kind of husband and father he was. These women were living lives of single motherhood despite the fact that they were actually married.

Another big problem is the dishonesty involved in these polygamous marriages. During Joseph Smith’s lifetime and for decades after his death, the official church narrative was that Joseph Smith had one, and only one, wife. This can no longer be the official narrative because of the amount of documentation showing that he had at least thirty-four wives. There are also many women rumored to be his wives in marriages for which there is no record, and when they are added to his list of wives there may be as many as forty-nine. At least eleven of his wives were married to someone else when marrying him, and it is questionable whether all their first husbands either knew or approved of the marriages. In one instance, Joseph married a woman in order to rescue her from the poverty she had fallen into while her husband was away serving as a missionary in Jerusalem, where Joseph had sent him.

The reasons given for the practice of polygamy are varied and mostly questionable. The main reason I always heard for the polygamy in Nauvoo and Utah was the need of husbands for women who had been widowed while travelling in Mormon caravans to these new locations. However, census data and church records from the 1840s and 1850s in Hancock County, Illinois, and in Utah show that there was no shortage of marriageable men in either place. In both places, there were more marriage-aged men than women during that time. Also, if there were widows in need of financial help, there were much more practical ways of supplying welfare to them without forcing them into loveless marriages.

Another reason for polygamy was the belief fostered by Joseph Smith that numerous wives would secure a “special place in heaven” for a polygamous man. I often wonder how they believed their many divorces from plural wives would affect this “special place in heaven.” There were numerous plural marriages ending in divorce, often on grounds of non-support, which also defies the reasoning that these marriages were made in order to give support to widows.

When asking young women to become plural wives, Joseph Smith would often take advantage of their zeal for their new religion and tell them that he had received a revelation telling him that Joseph not marrying a certain women would offend God and that God would send down an avenging angel with a sword to strike Joseph down. They married him in order to save him from the wrath of God.

Later, in Utah, whenever an older beloved colleague of Brigham Young felt the need to add a specific young wife to his family, Brigham would command the young woman’s parents to instruct the young woman to marry the older man, despite the fact that the young woman may have been already engaged to a young man closer to her own age and more suited for a happy marriage. Failure to follow these commands of Brigham Young could result in banishment, which in the hostile terrain of the Utah Territory could possibly be a death sentence.

Finally, it is bothersome that so many of these marriages were not based in love. The women in these marriages were trophy wives. The more wives a man had, the higher his social status was. You don’t see any mention of love when these marriages are mentioned in these men’s personal journals, only a reference to the “patriarchal order of marriage.”

This tree shows my descent from Catherine Reese and Zephaniah Clawson.

I have stated before that as the descendant of many plural marriages, I would not be here if it weren’t for the practice of polygamy, but I still often wonder whether my existence is worth the amount of unnecessary heartache and pain it caused for so many people.

copyright © 2019 Eric Christensen