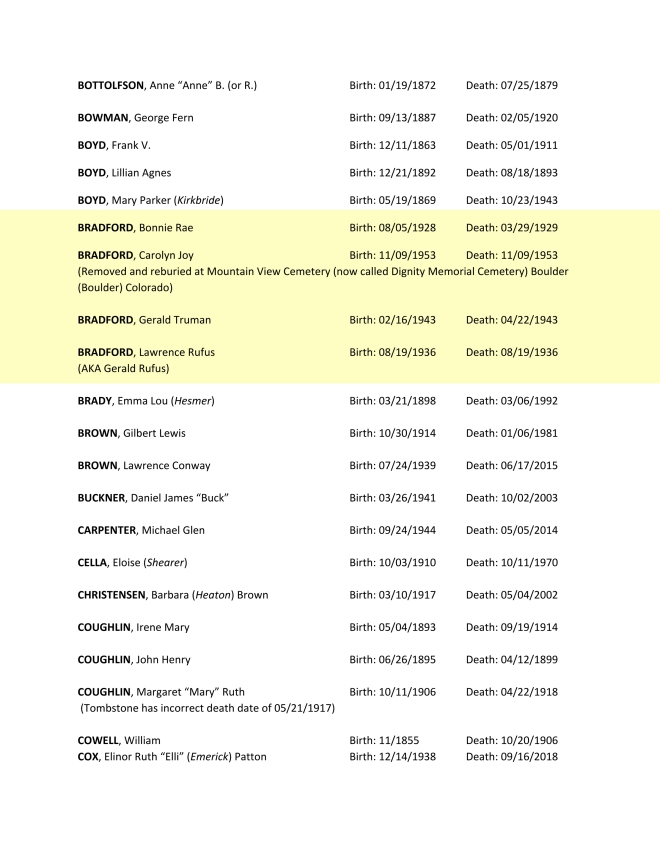

I refer to this collection of narratives as “Stories of my Family,” but I often find myself writing about people who are not actually related to me. They sometimes are people who have crossed paths with my family, but in this case they are not at all related, just a family whose history involves a neighboring town. Perhaps I need to redefine the term family to include members of my geographic community.

While walking through Gold Hill (Colorado) Cemetery in 2020, I came upon the graves of three children named Bradford who had all died as infants during the first half of the 20th Century. Their grave markers looked quite new, indicating that they must have been replaced since the Four Mile Canyon Fire had swept through the Gold Hill neighborhood in 2010. Someone today knows who these children were and cares about them. There were no other Bradford graves nearby, so I wondered how they came to be buried in Gold Hill. After a bit of research, I discovered who their parents were and how they fit into the history of the town.

The Bradford Children

The three Bradford children buried together are Bonnie Rae Bradford (08/05/1928–03/29/1929), Lawrence Rufus Bradford (aka Gerald Rufus Bradford; 08/19/1936–08/19/1936), and Gerald Truman Bradford (02/16/1943–04/22/1943). The crosses marking their graves are made of copper-colored pipes and pipe fittings, with name plates attached and white stones arranged at their bases, obviously too new looking to have survived the 2010 fire without damage. There is also a fourth Bradford child listed in the Gold Hill Cemetery Burial Index, Carolyn Joy Bradford (11/09/1953–11/09/1953), who was later removed and reburied at Mountain View Memorial Park in Boulder, down Sunshine Canyon from Gold Hill. I later determined that she was a niece to the other three Bradford children, the daughter of their brother Richard Charles Bradford (06/12/1930–01/12/1977).

After determining that these three children were children of Harlie Elmer Bradford (11/14/1909–10/01/1982) and Elizabeth Anne Nichols (12/17/1911–03/01/1994), I created memorials for them on Find-a-Grave. It was through these memorial pages that a member of the family (related by marriage) contacted me to inform me the children were buried next to their maternal great-grandparents, Edwin David “Ned” Goudge (01/09/1853–08/04/1923) and Annie Bennet Goudge (04/06/1856–09/09/1930), who had been early settlers in Gold Hill. (The birth dates of Edwin and Annie Goudge come from their funeral records. Other documents show various other years, so they might not be completely accurate.)

Parents: Harlie and Ann Bradford

Harley (later known as Harlie) Elmer Bradford was born in Bogue, Kansas, and moved to Colorado with his parents as a child. He married Elizabeth Anne Nichols (also known as Anne Elizabeth) in Littleton, Colorado, on August 12, 1927, and they settled in Boulder, Colorado, where he worked as a real estate broker. Elizabeth Anne Nichols was born in Gold Hill. Her parents probably lived in Salina at the time, about halfway down Four Mile Canyon from Gold Hill. Harlie and Elizabeth had eight children together, five of whom survived to adulthood. I have since learned (see the comments to this post below) that one of their sisters has kept a promise to her mother that she would update their graves. Harlie and Elizabeth both died in Boulder, where they are buried together in Mountain View Memorial Park. Elizabeth’s headstone shows her name as “Anne E.”

Maternal Grandparents: Richard and Ethel Nichols

The name Nichols has evolved over the years, and in various documents it is spelled Nichols, Nicholls, or Nicholas, and these variations in spellings still persist today. I will simply use the spelling Nichols for the sake of consistency.

Richard John Nichols (12/04/1887–09/24/1941) was born in Ophir, Utah, and he was merely a toddler when his family moved to Boulder County, Colorado. He married Ethel Goudge (10/15/1892–07/14/1981) in Boulder on April 9, 1910. Ethel had been born and raised in Gold Hill. Richard held various jobs in the mining industry, and they lived sometimes in Boulder, sometimes in Gold Hill, and sometimes somewhere in between. They raised two daughters together. Richard and Ethel both died in Boulder. Richard is buried in Gold Hill. Ethel, who outlived him by nearly thirty years, was cremated and is inurned in Mountain View Memorial Park in Boulder.

Maternal Great-Grandparents:

Edwin and Annie Goudge

Edwin David Goudge was born in Galena, Illinois, to English immigrants John and Harriet Wicks Goudge. Annie Bennet (also spelled Bennett) was born in England to John and Amelia Bennet, and immigrated to the United States as a child with her parents. Edwin and Annie were married in Randolph, New Jersey, on August 1, 1874. They visited Colorado on their honeymoon, fell in love with the state and its mountains, and finally settled in Gold Hill, where Edwin worked as a miner.

In 1900, Edwin and Annie purchased the Gold Hill Hotel (earlier known as the Kinney House, the Grand Mountain Hotel, and the Wentworth Hotel) and reopened it as the Goudge Hotel. In 1920, the Holiday House Association of Chicago, a women’s club offering therapeutic mountain getaways for working girls from the big city, purchased the Goudge Hotel from them. The organization was also known as the Bluebirds, and the hotel became the Bluebird Lodge. In 1927, the Bluebirds mounted a fund-raising campaign for the construction of a log recreation and dining hall adjacent to the Bluebird Lodge, which later became the Gold Hill Inn, an extremely popular dining establishment in Boulder County.

Edwin and Annie raised eight children in Gold Hill, and they remained in Gold Hill for the remainder of their lives. They are buried together in the Gold Hill Cemetery.

Eric Christensen