Tracing family history can be very confusing when a family name changes from one generation to the next. This can happen for a variety of reasons, sometimes intentional and sometimes accidental. As an example of an intentional change, when my Danish first-cousin-four-times-removed Niels Christensen moved to Elsinore, Utah, a town populated with Danish immigrants, he said, “We soon found it difficult to receive our mail, because so many families had the surname of Christensen. So, we decided to change our surname to Lee. Hence forth, we were known as Christensen Lee.” As an example of an accidental change, my Danish second-great-grandfather Peter Christian Christensen was born with the name Hans Peter Christensen. His parents and infant brother all contracted dysentery en route to America and died before reaching their final destination, so Hans Peter Christensen arrived in Saint Louis as a three-year-old orphan known only by his middle name. During his childhood he used the first name of Peter and took the last names of his foster families, first Forsgren and then Lowry. While preparing to be married, he discovered some family belongings indicating that his father’s name had been Christian Christensen, so he took the name Peter Christian Christensen in honor of his father, and he used that as his name for the remainder of his life, although he was usually referred to as P.C. Christensen.

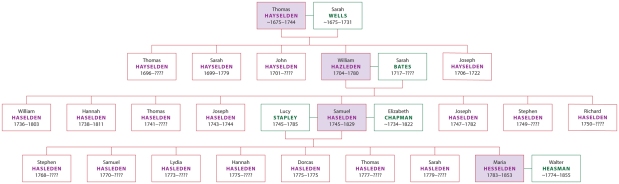

In this narrative, I will demonstrate how the last name of my English eighth-great-grandfather Thomas Hayselden changed over three generations, ending with his great-granddaughter’s name of Maria Hesselden. Although people give varied reasons for name changes, I believe that in this case the main reason was illiteracy, as evidenced by the fact that most of them signed their marriage records with their “marks,” indicating that they could neither read nor write. Therefore, their names on baptism, marriage, and burial records would have been spelled however the parish clerks filling out the records thought they should be spelled.

The name itself is believed to have come from the Medieval English words hoesel, meaning hazel, and denu, meaning valley, so it would be a habitational name used by someone living in a valley where hazel trees grow. The parish records I have used to follow the name were often written with poor penmanship, so I hope that I have correctly interpreted the handwriting from most of the records.

First Generation: Thomas Hayselden / Hyaselden / Hayslenden / Hasselden / Haselden

My eighth-great-grandfather Thomas Hayselden is estimated to have been born about 1675 in Mayfield, Weald District, East Sussex County, England. I could not find the record of his baptism, but the records where I could find his name were his marriage record, the records of his children’s baptisms, his wife’s burial record, and his own burial record. His name is Hayselden on the record of his marriage to Sarah Wells on April 12, 1696, in the Church of Saint Dunstan in Mayfield. His name had changed to Hasselden on the record of his wife’s burial on February 17, 1731, in Mayfield; and then to Haselden on the record of his own burial on November 16, 1744, in Mayfield.

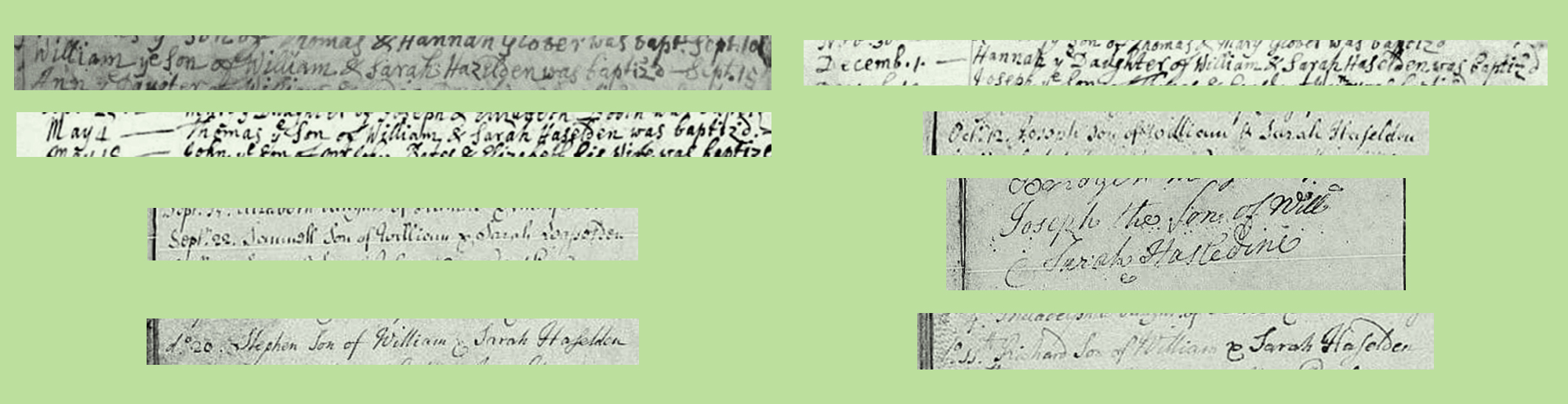

Thomas and Sarah had five children together, all baptized in the Church of Saint Dunstan in Mayfield: Thomas, baptized November 1, 1696; Sarah, baptized January 29, 1699; John, baptized, March 30, 1701; William, baptized April 30, 1704; and Joseph, baptized March 3, 1706. The last name shows on their baptism records as Hayselden (Thomas, Sarah, and John), Hyaselden (William), and Hayslenden (Joseph).

Second Generation: William Hayselden / Hyaselden / Hazelden / Haselden / Hasselden / Hazleden

My seventh-great-grandfather William Hazleden was baptized April 30, 1704, in the Church of Saint Dunston in Mayfield. I could not find an image of his original marriage record, but an online source names “Sussex Marriage Records” for documentation of his marriage to Sarah Bates on January 7, 1735, in Battle, Rother District, East Sussex County, England. They began their married life in Northiam, Rother District, East Sussex County, England—probably his wife’s home town—where their first three children were born. They later returned to his home town of Mayfield, where their remaining five children were born. His last name on his baptism record was Hyaselden) (as shown above). His name had changed to Hazleden on the record of his burial record on April 13, 1780, in Mayfield. I could not find a record of his wife’s burial.

William and Sarah had eight children together, the first three baptized in Northiam, and the last five baptized in the Church of Saint Dunston in Mayfield: William, baptized September 15, 1736; Hannah, baptized December 1, 1738; Thomas, baptized May 4, 1741; Joseph, baptized October 12, 1743; Samuel, baptized September 22, 1745; Joseph (after the first Joseph had died), baptized March 17, 1747; Stephen, baptized February 20, 1749; and Richard, baptized November 11, 1750. The last name shows on their baptism records as Hazelden (William), Haselden (Hannah, Thomas, 1st Joseph, Stephen, and Richard), Hasselden (Samuel), and Hasledine (2nd Joseph). The last name on some other records for these children also include many of these variations, but I will document only those for Samuel, who is my direct ancestor.

Third Generation: Samuel Haselden / Hasselden / Hasleden

My sixth-great-grandfather Samuel Haselden was baptized September 22, 1745, in the Church of Saint Dunston in Mayfield. He was first married to Lucy (aka Lucia) Stapley. Lucy predeceased him, after which he married his second wife, Elizabeth Chapman (widowed, maiden name unknown). Elizabeth also predeceased him. The last name on his baptism record is Hasselden (as shown above). His name had changed to Haselden on the record of his first marriage on October 19, 1767, in Guestling, Rother District, East Essex, England; then to Hasleden on the burial record of his first wife on July 26, 1785, in Guestling; and remained Hasleden on the records of his second marriage on May 3, 1786, in Guestling; on the burial record of his second wife on February 28, 1822, in Guestling; and on the record of his own burial on May 6, 1829, in Guestling.

Samuel and Lucy/Lucia had eight children together, all baptized in Guestling: Stephen, baptized May 8, 1768; Samuel, baptized July 8, 1770; Lydia, baptized February 14, 1773; Twins Dorcas and Hannah, baptized June 18, 1775; Thomas, baptized June 22, 1777; Sarah, baptized December 14, 1779; and Maria, baptized June 22, 1783. The last name shows as Hasleden on all of their baptism records.

Fourth Generation: Maria Hasleden / Hesselden

My fifth-great-grandmother Maria Hesselden was baptized June 22, 1783, in Guestling. The last name on her baptism record is Hasleden. Her name had changed to Hesselden on the records of her marriage to Walter Heasman on January 24, 1801, in Icklesham, Rother District, East Essex, England. All later records show her with her married name of Heasman, so there are no additional variations of her maiden name.

And thus ends the documentation of the changing of a name over four generations. I have not followed the siblings of Maria Hesselden to determine whether their names have undergone any additional changes.

My Descent from Maria Hesselden

Maria Hesselden (1783–1853) and Walter Heasman (~1774–1855) were the parents of Ann Heasman (1801–1882). Ann Heasman and Thomas Baker (1794–????) were the parents of Caroline Baker (1824–1904). Caroline Baker and William Crouch (1821–1899)—the first generation of this line to immigrate to the United States with their six children in 1873—were the parents of Emma Firetem Crouch (1857–1928). Emma Firetem Crouch and Willard Charles Burgon (1853–1919) were the parents of Minnie Josephine Burgon (1878–1946). Minnie Josephine Burgon and William Moroni Cox (1881–1958) were the parents of Reba Cox (1909–1999). Reba Cox and Theodore Angelo Christensen (1903–1981) were the parents of Theodore Paul Christensen (1929–2011). Theodore Paul Christensen and Carol Madsen, were my parents.

Eric Christensen