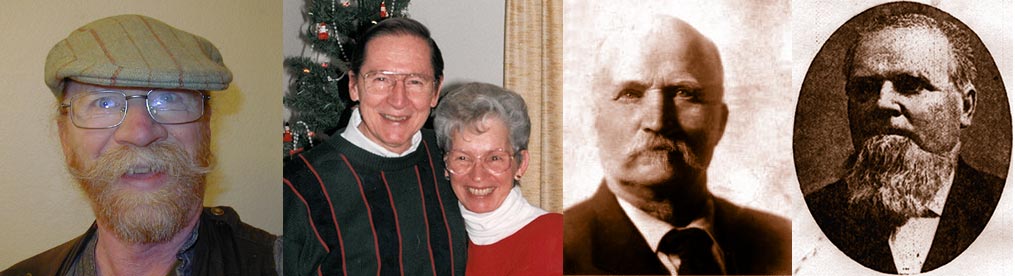

I am planning to write the most complete biographies possible about as many of my direct ancestors as I can. The first will be of my second great grandfather, Peter Christian Christensen. His story has been difficult to track down, because earlier genealogists have recorded a lot of incorrect information about him. I hope to make it as accurate as I can, and I welcome any input if anyone finds any inaccuracies.

[Footnotes with references are included at the end of each section. Some of them include links to online reference sites, and hopefully they will remain up to date. It is difficult to keep up with organizations constantly remaking their web pages. At the time of publication, the link for Dansk Demografisk Database was not working. I hope this is a temporary problem, as this is the only online source I know of for finding Danish census records.]

This tree shows my descent from Peter Christian Christensen.

Personal Data

Name: Peter Christian Christensen

Also Known As: Hans Peter Christensen

Also Known As: P.C. Christensen

Born: August 17, 1849, København, Kingdom of Denmark

Died: December 19, 1928, Moroni, Sanpete County, Utah, USA

Burial: December 21, 1928, Moroni City Cemetery, Moroni, Sanpete County, Utah, USA

Son of: Christian Christensen and Margrethe Hansdatter

Brother of: Johan Erastus “Jon” Christensen

Husband of: Mary Mallinson

Father of: Edward Christian Christensen (never married), Peter Angelo Christensen (married to Maren Regina Fechser), Blanche Ophelia Christensen (married to Oliver Eugene Eliason), Ernest Raymond Christensen (married to Crilla Ethelyn Candland), Hannah Caroline “Daisy” Christensen (married to John Raymond Blackham, widowed, married to Edgar Thomas Reid), Nelson Howard “Nels” Christensen (never married), Mary Viola “Shorty” Christensen ( married to Perry Taylor Warren, married to Oren Draper, remarried to Perry Taylor Warren), Randall “Ray” Christensen (married to Ida Belle Gledhill), Frank Jay Christensen (married to Violet Fiack [widow of Edmund T. Olsen]).

Early Childhood in Denmark

Peter’s parents were Christian Christensen (born March 4, 1819, in Kirke Såby, Voldborg, Roskilde, Denmark)1 and Margrethe Hansdatter (born April 26, 1826 in Skulleløv, Frederiksborg, Denmark).2 They were married September 16, 1849, in København, Denmark. At the time they were married, Christian was working as a farm hand.3 During the early years of their marriage, they lived in København, where Christian worked as a laborer in a soap factory.4

Peter was born August 17, 1849 in København, Denmark,5 approximately one month before his parents were married. He was baptized the same day as his parents’ marriage, and the moral judgment of the parish priest seems to be evident in the comment uægte [illegitimate] included in two separate places on Peter’s birth and baptism record. His name at birth was Hans Peter Christensen. Apparently, he was known by his middle name during his early years, because he spent the rest of his life as Peter, probably never knowing that his original name was Hans. He also spent his life thinking his birthday was December 5, 1849, which is the date of birth listed on his death certificate.

The naming convention in Denmark at that time was for the first-born son to be named after his paternal grandfather and for the second-born son to be named after his maternal grandfather. This might lead one to believe that Peter had an older brother named Christen. However, in some locations the naming convention might have been different for an illegitimate son, who would be named instead after his maternal grandfather.6 With this in mind, it can be assumed that Peter was the oldest son in the family.

When the Mormon missionary Johan Erik “John” Forsgren was banished from Sweden in 1850, he and his partner Erastus Snow continued their missionary work in København. There they converted Christian and Margrethe Christensen, who named their second son Johan “Jon” Erastus Christensen (born June 11, 1852) in honor of those two missionaries.7

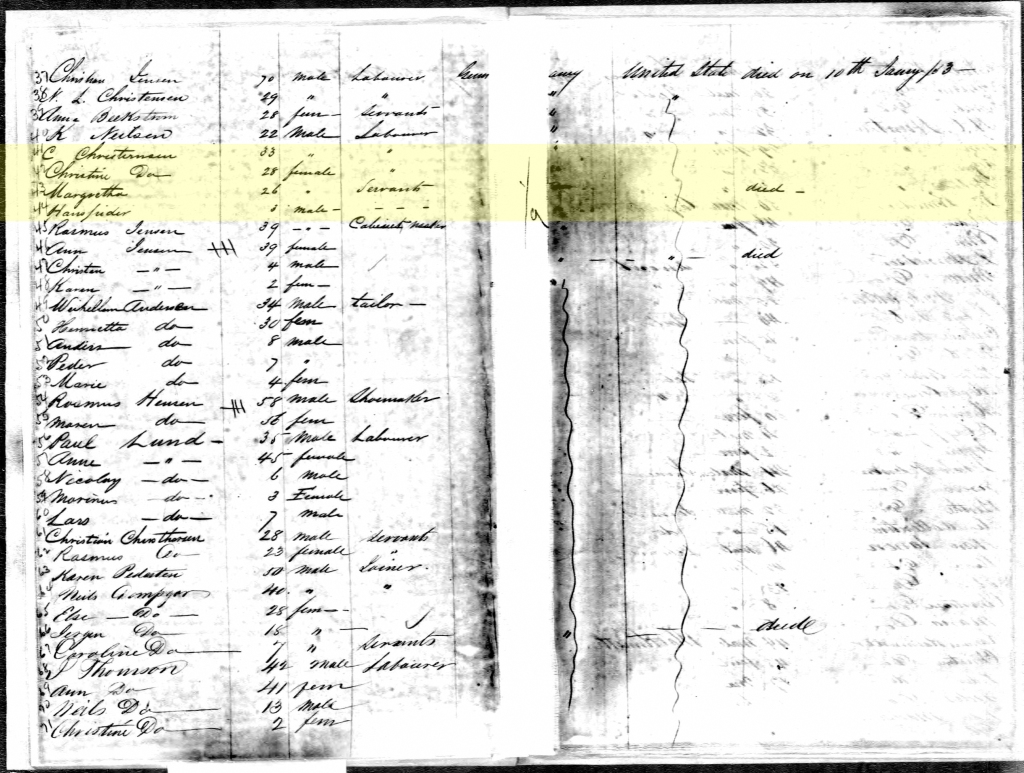

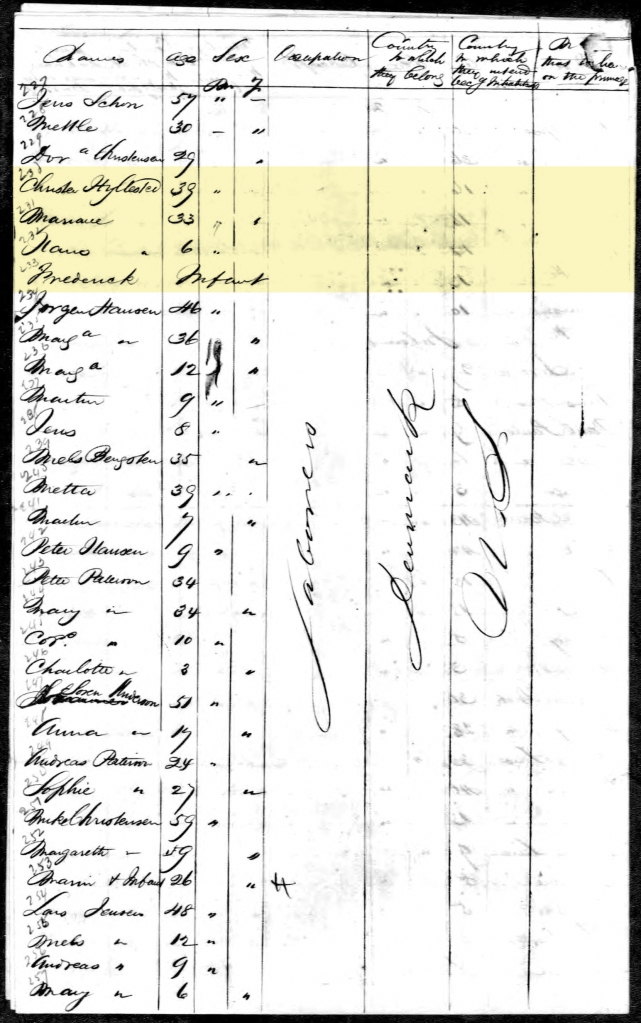

By late 1852, those who had joined the Mormon Church in Denmark were feeling like outcasts in the predominantly Lutheran Danish society. When John Forsgren was preparing for his return to Utah, he put together a company of 297 converts to join him. The people in this company sold their property for only a fraction of its value before they left. They were known as the “Scandinavian Mormon Migration,” the first large group of Mormons to travel from Denmark to the Great Salt Lake. Christian and Margrethe Christensen and their two sons were a part of this migration.

============

Footnotes for “Early Childhood in Denmark”:

1Christian Christensen’s date and place of birth come from a copy of his birth record accessed at Arkivalieronline, from a copy of his confirmation record shared on Ancestry, and from a transcript of the 1850 Danish census accessed at Dansk Demografisk Database.

2Margrethe Hansdatter’s date and place of birth come from copies of her birth and confirmation records shared on Ancestry, and from a transcript of the 1850 Danish census accessed at Dansk Demografisk Database.

3The date of their marriage and Christian’s occupation at the time come from a copy of their marriage record shared on Ancestry.

4This information comes from the Christian Neilson Journal and Letters, compiled by Christian Neilson’s second great granddaughter, Wanda Knudsen Guthrie, in which Christian Christensen is referred to as “Sobesyder [soap maker] Christensen.”

5Peter’s date and place of birth come from his birth and baptism record shared on Ancestry, and from a transcript of the 1850 Danish census accessed at Dansk Demografisk Database.

6This possible variation in the Danish naming convention was suggested by Bev Anderson in a forum discussion at Rootsweb.

7The story of the Christensens’ conversion, the birth of their second son, and their departure from Denmark come mostly from undocumented family trees and family histories. Jon’s year of birth can be calculated from the age given on his death record at the Missouri State Archives.

============

From Denmark to Saint Louis

Although there are no specific mentions of this Christensen family in the journals from the voyage (aside from the tragic deaths of three of them near the end of the journey), the following narrative gives an idea of what young Peter Christensen would have experienced during these months.

The voyage of the Scandinavian Mormons began on Monday, December 20, 1852.8 On this day, at 12:30 p.m., they sailed from København aboard the steamship Obetrit. They had to lay at anchor for most of the day on Tuesday and arrived in Kiel, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, on Wednesday. Being at sea for the first time, a large number of passengers suffered from seasickness during this short trip.

At 6:30 the following morning, they boarded a train at Kiel, arriving in Altona, Hamburg, Germany, at 9:30 that night. That trip along the Hamburg-Altona–Kiel railway of 105.6 kilometers (65.6 miles), which took them more than a half-day, would take just slightly more than an hour by automobile today. They were cordially received in Altona, where they were fed and given lodging for the night.

At 2:00 p.m. on Friday, Christmas Eve, they set sail on the steamship Løven [Lion]. When they reached Cuxhaven, Lower Saxony, Germany, at 8:45 p.m., they were forced to drop anchor until 1:00 Christmas afternoon because of stormy seas. Then they sailed along the coast to near Workum, Friesland, Netherland, where they were once again forced to drop anchor because of stormy seas.9 They could not sail again until midnight.

During the night of Sunday, December 26, the storms on the North Sea became so severe that all of the passengers had to remain in extremely tight quarters in the hold of the ship for nearly an entire day as the waves crashed over the deck. Tempers flared during these trying circumstances, and some minor fights erupted. When the storm finally ceased, they discovered that many boxes and barrels had been broken by the force of the waves, and apples were strewn all over the deck. To the children’s delight, they were told they could eat as many of the apples as they wanted. Many children ate more than they should have and regretted it later.10 The sailors rigged up a rope railing to replace some of the railing that had been destroyed in the storm.

After two days on stormy seas, the ship arrived at Hull, York, England, on Tuesday, December 28. The captain said it was the worst storm he had ever been out in. More than a hundred ships had been damaged or destroyed.

At noon on Wednesday, December 29, they caught the train to Liverpool, Merseyside, England, and reached their destination at 9:00 that evening. They were warmly received there, and they were fed and given lodging for the night. They remained there for one additional day.

On Friday, New Year’s Eve, they finally boarded the ship that would take them to America. The Forest Monarch, under the command of Captain Edmund Brewer, was a Canadian-built, three-masted square-rigger, usually employed as a packet ship.11 Today, it would be considered a small ship, but it seemed enormous to the travelers of the time.

The Danish voyagers spent the first two weeks of 1853 on board the Forest Monarch anchored in the River Mersey, waiting for friendly winds to replace the storms. They would often dance and sing for recreation to pass the long days of waiting. A daughter, Josephine Ipsen, was born to passengers Anders and Kristine Ipsen during that time. A daughter, Hannah Josephine Andersen, was born to passengers Wilhelm “William” and Henrietta Andersen on Saturday, January 1. Passenger Juliane Knudson, who had remained behind in Hamburg because of illness, finally caught up and rejoined the other passengers on Monday, January 3. On Friday, January 7, the passengers held a meeting to discuss regulations concerning the preparation of food, the cleaning of the ship, and the distribution of water. Four couples were married on Saturday, January 8. Passenger Christen Jensen, eighty-five and a half years old, died on Monday, January 10, and his body was taken ashore for burial. There were two additional deaths on Wednesday, January 12: (1) passenger Christian Neilsen, twenty-six years old; and (2) Lauritz Elias Domgaard, young son of passenger Niels Peter Domgaard. Their bodies were taken ashore the following day for burial in Liverpool. At one point during their wait, the Forest Monarch was struck by another ship but suffered only minor damage. On another night, stormy waters set the Forest Monarch adrift, and she had to be rescued by two tug boats.

On Sunday morning, January 16th, they finally lifted anchor so they could begin their journey across the ocean. From noon until 4:00, a tugboat pulled them up the River Mersey, and they watched Liverpool disappear into the fog. For the next two days, the winds were favorable as they sailed through Saint George’s Channel and into the North Atlantic Ocean.

As they started across the ocean, the weather was mostly good, sometimes warm enough for people to walk on the deck in light clothing and bare-footed. Nevertheless, an occasional stormy day would damage the sails and leave some of the passengers seasick. From the deck, they could see many other ships, and sometimes they could watch large flying fish and dolphins swimming.

On Thursday, February 3, infant Josephine Ipsen, who had been born while the Forest Monarch was anchored in the River Mersey, died and was buried at sea. On Monday, February 7, Poul Poulson, the infant son of Anders and Bodila Poulson, died and was buried at sea.12 A daughter, Geraldine Hansen, was born to passengers Jens and Sophie Hansen during the night of Monday, February 14.

On Tuesday, February 15, the Danish immigrants caught their first view of the West Indies as they passed by La Désirade in the Guadeloupe island group. That evening, a son, Ephraim Larsen, was born to Poul Christian and Kirsten Larsen. The passengers watched large flocks of birds that would fly down to pick food from the surface of the water. A swallow flew onto the ship and stayed for the day. On Monday, February 21, Anna Maria Ipsen (three-year-old sister of Josephine Ipsen, who had died on February 3) died and was buried at sea.

On Thursday, February 24, they passed Jamaica and could see Cuba to the north. The passing took some time, as the winds were slow that day. The next day, they traveled far enough that they could no longer see Jamaica. On Sunday, February 27, and Monday, February 28, they could see a beacon of light from a lighthouse on Cuba. Monday evening, Ephraim Larsen, the youngest child aboard the ship, died.13

From Tuesday, March 1, through Saturday, March 5, contrary winds made for slow progress, but they were finally able to drop anchor at the mouth of the Mississippi River on Monday, March 7, and John Forsgren went ashore to New Orleans to make preparations for the trip up the Mississippi. That evening, passenger Maren Jorgensen died. A small group of men made a casket and took her body to a small island near the mainland for burial. When they returned to the ship, they brought green tree branches and green plants, which was a refreshing sight to the immigrants who had spent the last two months on the ocean.

The island where they buried Maren Jorgensen is important to this story, as this is where Margrethe Hansdatter Christensen, the mother of Peter Christian Christensen, would also be buried less than a week later. The location of the actual island will probably never be positively identified. Their description of it said only that there were many tree stumps, that the land was very rich, and that it had a lighthouse. A total of five passengers died while they were waiting at anchor, and most if not all of them were buried on the same island. Perhaps some had been on the verge of death but willed themselves to remain alive until they saw America; or, perhaps, the water supplies going rancid during the long voyage finally caught up with them. Some of the passengers remaining on the ship were suffering from dehydration and dysentery.

On Friday, March 11, Louise Marie Pedersen, the infant daughter of passengers Hans and Ane Martine Pedersen, died and was buried on the same island.

Peter Christensen’s mother, Margrethe Hansdatter Christensen, died on Saturday, March 12. Some journals say that she died in the evening, while others say she died at 5:00 in the morning, but they all agree on the date. There is no official record of her death, but it would be assumed that the cause of death was dysentery. She was buried on the same island as Maren Jorgensen and Louise Marie Pedersen, so her remains are now in an unknown place. That evening, John Forsgren returned from New Orleans on a steamship, bringing fresh meat, vegetables, and bread that he distributed among the passengers.

On Sunday, March 13, passenger Anders Ibsen died and was buried on the same island. Two of his daughters had died during the previous month. On Tuesday, March 15, Jens Christian Jensen, four-year-old son of passengers Mads Christian and Maren Jensen, died. He may have been buried on the island, or he may have been buried in the Mississippi River.14

On Tuesday, March 15, when the river was high enough that the ship wouldn’t get stuck on the muddy river bottom, two steamboats hauled the Forest Monarch farther up the river. After some of the passengers were transferred to a larger ship and reluctantly required to mix with passengers of different nationalities and religions, they docked in New Orleans on Thursday, March 17, at 10:30 a.m. Although the immigrants who had been transferred felt persecuted by the other passengers, they were counseled by John Forsgren to “return good for evil,” and they agreed to present to the captain of that ship a gift of twelve American dollars in an attempt to improve the impression most people had of the Mormons. As they approached New Orleans, on the east side of the river they could see black slaves and their white overseers working in the beet fields and living in wooden shacks and houseboats. Most of the shacks were built on poles so they would be high enough when the river overflowed its banks. On the west side of the river, they could see a lighthouse and some factories. Closer to town, they could see finer houses with orchards, flowering gardens, livestock, and birds singing in the trees. They passed by a church and saw people driving closed-in wagons. It looked like paradise to those who had been at sea for such a long time.

They were docked in New Orleans for a very short time. Some of the passengers took advantage of this opportunity to set foot on American soil for the first time, but John Forsgren advised them against going into town, because he felt it was populated by “ungodly people.” Some local Danish people came aboard to ask about the latest news from Denmark and to see if they knew anyone on the ship. Two passengers, identified only as “W. Andersen and his wife,” parted company with the Mormons and chose to remain in New Orleans. Two children died during this short stay and were buried in New Orleans: (1) Margrete Christina Larsen, three-year-old daughter of passengers Hans and Elina Larsen; and (2) Christina Margrethe Munk, infant daughter of Christian and Anna Maria Munk. One child, Ephraim Monarch Dennisen, son of Hans and Johanna Dennisen, was born during this time.

On Saturday, March 19, the passengers boarded a small steamship, which was used to transfer them to a larger steamship, the Grantover. During this transfer, Chistian Christensen was very ill, and was accompanied by Christina Erika Forsgren (sister of John Forsgren, the group’s leader), who was helping to take care of young Peter and Jon Christensen, whose mother had died less than a week earlier.15 Two other passengers, twenty-eight-year-old Anna Beckström, and eight-year-old Peter Munk, were also quite ill at this time, but both soon recovered.

The Grantover was a three-decker, which looked like a large, flat, three-story building floating up the river. It was more than one-and-a-half times longer than the Forest Monarch. The pilot steered the ship from a salon at the front, where many sailors had to keep watch for logs or branches floating down the river that could threaten to damage the paddlewheels. The passengers were quartered in the lower deck, but the cargo of many large sacks of salt left very little room for them to sleep. Some of the passengers searched around the ship in order to lay claim to more comfortable places to sleep.

On Sunday, March 20, the ship stopped to take on an additional cargo of sugar. The freight took up so much room that the Mormons could not find a space large enough to hold their regular Sunday meeting. From the deck, they could see many houses, gardens, and orchards, and people fishing from the river bank. They could also see many smaller boats, built for housekeeping as well as for sailing, floating into the Mississippi from its tributaries.

On Monday, March 21, through Saturday, March 26, they passed by some large forests, some areas of which had been cleared of trees and with the ground plants burned off in order to prepare the land for farming. They could see some small villages, as well as large plantations with small decrepit shacks for the slaves’ quarters. Beside them on the river, they were able to see many different styles of steamships, some with paddlewheels in the back and some with paddlewheels in the center of the ship.

On Easter Sunday, March 27, they still did not have room to hold a Sunday service. The following day, they stopped in a small town, where they could see factories, a saw mill, and coal mines. Here, they took on even more cargo consisting of packed barrels and other merchandise.

On Tuesday, March 29, they arrived in Saint Louis, Missouri. From the deck, they could see a large steamship serving as a ferry that was large enough to take full wagons and their teams across the Mississippi River. They were beginning to witness first-hand that America was the land of opportunity. The working men in Saint Louis were better dressed than the best-dressed people in Denmark. At meal time, the American sailors aboard the ship were served as much food as they wanted, and if there was more than they could finish it was thrown overboard. When they left the ship on Wednesday, March 30, Christian Christensen was still very ill. Passenger N. Hansen was also ill.

When they left the ship, it was determined that it would be healthier to remain in Saint Louis for a while before continuing their journey, so they paid their lodging for a month on the second floor of a four-story building, packing as many of them in a room as could fit. Many of the men went to work during this stay, some working on grading of a new railroad. There were many houses built of wooden boards in Saint Louis, and the immigrants witnessed more than a few house fires while they were there. The parks in the city had artificial water springs to which the fire department would attach long hoses in order to fight the fires. The parks were well cared for, but the immigrants were surprised at the lack of sanitation on the city streets and the lack of upkeep in the city’s cemeteries.

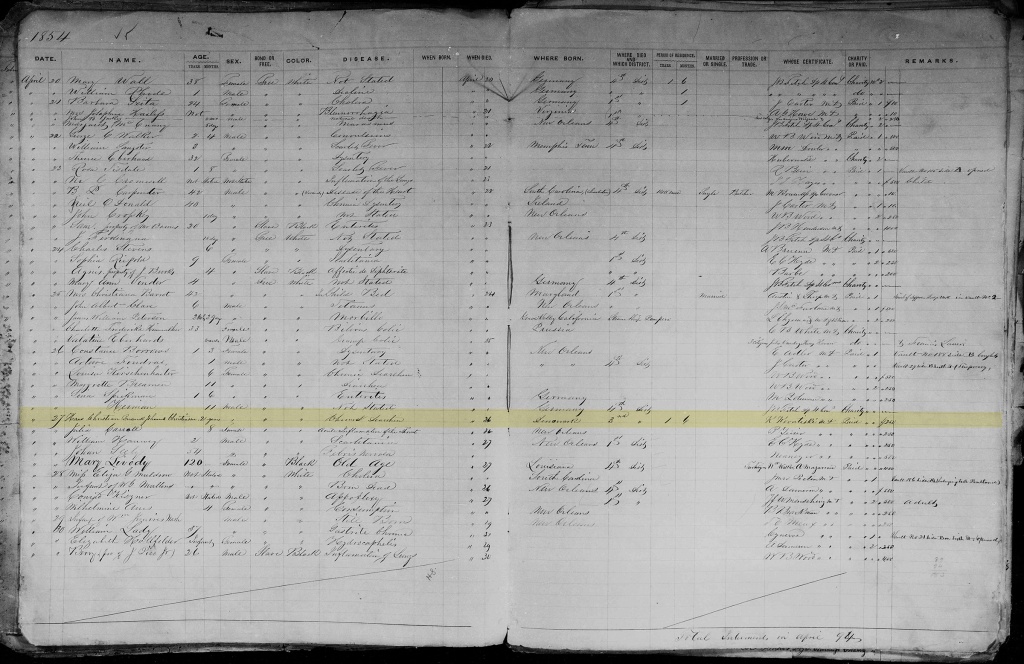

On Saturday, April 2, Peter Christensen’s infant brother, Jon, died of dysentery and was buried in Wesleyan Cemetery.16 Wesleyan Cemetery later closed in 1878 and relocated to the New Wesleyan Cemetery, then closed again in 1952 and relocated to various other cemeteries.17 The graves of those with no known descendants were not recorded, so Jon’s remains are now in an unknown location.

The following day, Sunday, April 3, Peter Christensen’s father, Christian Christensen, died of dysentery and was buried in a pauper’s grave at Saint Louis City Cemetery.18 Inger Dennison, whose grandson Ephraim had been born while the Forest Monarch was docked in New Orleans, died the same day of old age and was also buried in a pauper’s grave at City Cemetery. There were three cemeteries known as City Cemetery in Saint Louis, but they no longer exist. Most of the graves are said to have been moved to New Pickers Cemetery, a part of Gatewood Cemetery, and there are no markers for the graves moved from the City Cemeteries.19 Christian Christensen’s remains are now in an unknown location.

At the age of three, in a strange land, not yet knowing the language of his new country, Peter Christensen became an orphan. Surviving family members, if any existed, were thousands of miles away in Denmark. He was truly alone in the world.

On the evening of April 3, three of the immigrant couples were married, so life went on as usual. On Friday, April 8, passenger Anders Beckström from Sweden, who during the journey had lost his memory, died in a hospital in Saint Louis. He was one of the few non-Mormons to travel with the group.

============

Footnotes for “From Denmark to Saint Louis”:

8The stories of the journey from Denmark to Utah are documented in various journals kept by member of the company. Most of them can be accessed at Mormon Migration or at Mormon Overland Pioneer Travel. Family trees at Ancestry (some documented, some not) have been used to try to fill in the entire names of those passengers who have been identified in the journals only by partial names.

9The journal of an unidentified Danish immigrant states that they dropped anchor at “Nye Werk, Holland.” Workum seems to be the most likely city close enough to the coast for him to be referring to. The journal does not make it clear how long it took to get from Cuxhaven to there, so it is hard to gauge whether the timing is right for this to be case.

10This story comes from The Autobiography of Caroline Domgaard Nelson or Neilsen (although titled Autobiography, it is actually written in the third person and appears to be written by someone else), who was seven years old at the time. It was accessed at Autobiography of Caroline Domgaard Nelson or Nielsen. The story quotes Peter Munk, who was eight years old at the time. Caroline Domgaard and Peter Munk were both passengers on the ship.

11Information about the Forest Monarch comes from Scandinavian Emigrant Ships.

12One passenger’s journal stated that the son of Poul Larson died on March 15, but he may have been mistaken, because other journals give the date as February 7.

13The journal of Christian Neilsen Munk states that the child who died that evening was the “child of Brother Christensen.” The other journals, however, refer to him as the “child of Brother Pouls Chr. Larsen” or as the “youngest child on the ship.” Either Christian Munk made a mistake with the name in his journal, or (more likely) a transcriber got it wrong.

14It seems strange for someone to be buried “at sea” in a shallow portion of the Mississippi River, so it may or may not be true. One immigrant’s journal simply says “the body was buried.” Another says he was “buried at sea.” A third says he was “buried in the river.”

15The assumption that Christina Forsgren was with the Christensen family is deduced from the following: (1) the list of passengers leaving the Forest Monarch shows a Christine with the Christensen family; (2) Christensen family histories say that the orphaned Peter was taken in by the Forsgren family; (3) Forsgren family histories say that Christina Forsgren was aboard this ship; and (4) Christina’s name cannot be found elsewhere on the list of departing passengers. The only other possibility for the Christine leaving the ship with the Christensens would be Anna Christine Knudsen, who later married John Forsgren’s brother Peter, but she can be seen elsewhere on this passenger list with her parents, so this couldn’t be her.

16The cause of death and place of burial come from death records obtained from the Missouri State Archives.

17Information about the history of Wesleyan Cemetery comes from the Saint Louis County Library web site and from the Find-a-Grave web site.

18The cause of death and place of burial come from death records obtained from the Missouri State Archives. This particular record contains some errors. It lists Christian Christensen as female rather than male. Also, in the entry directly below his, it lists Inger Dennisen as male rather than female, although the journals of other passengers refer to her as “Sister Dennisen” and “the mother of Brother Dennisen.” Curiously, she is also designated as male on the list of passengers leaving the Forest Monarch, but many irregularities on that record can be attributed to the language barrier between the workers in New Orleans and the Danish passengers they were recording. She was probably ill at that time and had someone else providing her information.

19The information about the City Cemeteries in Saint Louis comes from the Find-a-Grave web site, and is attributed to the St. Louis Genealogical Society.

============

From Saint Louis to Sanpete County

The Christensen family histories all say that Peter Christensen crossed the plains with the company led by John Forsgren made up of the passengers from the Forest Monarch. There is no reason to doubt that three-year-old Peter was a member of this company, but he doesn’t seem to appear in any surviving records of the journey. Perhaps as a young orphan, he was like a shadow in the group, being there but never really noticed. The family histories say he was taken in by John Forsgren. Research indicates that John Forsgren didn’t treat his own families very well, so it might be out of character for him to volunteer to take in an orphan, but that is apparently what happened. Perhaps Peter was cared for by John Forsgren’s sister Christina during this leg of the journey.

At their regular Sunday meeting on April 10, the immigrants signified by a show of hands that they were ready to travel to Keokuk, Iowa, their next leg of the journey.

On Thursday, April 21, the first half of the Forsgren Company left for Keokuk on the steamship Di Vernon, sailing up the Mississippi River and arriving the following day. They stayed for one night in Keokuk, then set up camp about a mile north of the town near a forested area where they could collect all of the firewood they would need. There was a camp of English immigrants who had prepared their camp site and helped them get settled in their quarters.

The same day that they left, a daughter, Josephine Epraimine, was born to Peter and Ellen Madsen in Saint Louis, but she died nine days later, Saturday, April 30, and was buried the same day. On Sunday, April 24, Kirsten Larsen, the wife of Poul Christian Larsen, died in Saint Louis, and she was buried two days later, Tuesday, April 26, the same day that John Forsgren returned to help the second half of the company prepare to travel to Keokuk. On Friday, April 29, Christina Maria Christiansen, wife of Christian Christiansen (no relation to Peter Christensen), gave birth to stillborn twins near Keokuk.20

The second half of the company departed for Keokuk on Saturday, April 30, except for Peter and Ellen Madsen, who buried their nine-day-old daughter that afternoon and left the next day. After spending the night in Keokuk, they joined the first half of the company in the camp north of town. Following a proposal from John Forsgren, Hans Christian Hansen, who had served in the Danish Army before leaving his homeland and been a close personal friend of Danish King Frederick VII, was unanimously appointed to be the sergeant of the camp.

On Sunday, May 8, Peter Adolph Forsgren, the brother of John Forsgren, was married to Kirsten Knudsen.

During the weeks they were in Keokuk, much energy was put into procuring wagons, oxen, and supplies. The group was divided into companies of fifty, each divided into five companies of ten. A captain was appointed for each ten and an additional captain over each fifty. John Forsgren was appointed captain over the entire Danish company.

On Monday, May 16, John Forsgren left to obtain some more oxen. On Tuesday, May 17, a child of Rasmus Andersen died. On Wednesday, May 18, John Forsgren returned with some oxen.

On Friday, May 20, the first group left Keokuk, and camped about ten miles away. They traveled another four miles on Saturday, May 21, and made a new camp. John Forsgren and Christian Christiansen then returned to Keokuk to lead the remaining members of the company to this camp, who arrived on Sunday, May 22. It was a rough start to their journey, as it rained most of the time they were traveling. On May 22, a child was born to a member of the company identified only as “Sister Andersen.”21

On Friday, May 23, they camped at Sugar Creek, Iowa. This spot, about seven miles from Nauvoo, Illinois, had been used as a winter camp by the first Mormon company to cross the plains and was referred to by them as the “Camp of Israel.” Nearly all the early Mormon companies camped at this site.22 While they were there, the members of the company agreed that if they had enough provisions they should give a present to the leader of the English camp who had helped them get settled at Keokuk.

On Tuesday, May 31, the company began to travel again, but Lars Justesen’s group of fifty was delayed while they rounded up some lost oxen. Paul Kofford’s wagon tipped over in a ditch while two women and two children were riding in it. Luckily, no one was hurt, and the wagon was not damaged.

On Wednesday, June 1, Lars Justesen’s group of fifty caught up with the company. On Thursday, June 2, they passed near a place known as Dogs Town and camped not far from it. On Sunday, June 5, they experienced a lot of rain and hail along with thunder and lightning. John Forsgren injured his arm and back when he slipped in the mud and fell under a wagon. The rain continued Monday, June 6, through Wednesday, June 8, as they passed through Stringtown and Drakesville, Iowa. On Thursday, June 9, they camped at Soap Creek after passing through Unionville, Iowa. On Saturday, June 11, they camped at a place identified as “Doddirsjoid.” On Sunday, June 12, they camped east of Chariton Pond and passed by the town of Chariton the following day, Monday, June 13. A daughter, Sarah Florentine, was born to Herman Julius and Hannah Christensen.

After passing by Chariton, they spent the next few nights camping by small streams. On Thursday, June 16, after passing by Four Mile Stream and Seven Mile Stream, they camped near Mount Pisgah, which had been made into a permanent settlement for use as a stopping point for Mormon companies traveling west. Mount Pisgah had been named after the mountain in the Bible from which Moses was allowed to see the promised land.

On Saturday, June 18, and the following day, they camped on the Middle Branch of the Nodaway River. On Monday, June 20, they camped on the West Branch of the river. On Tuesday, June 21, they camped near Indiantown, Iowa. On Wednesday, June 22, they had to camp at a place where there wasn’t any firewood. The following morning, Thursday, June 23, they got a late start, as they had to wait for Lars Justesen to round up some missing horses. While crossing the Nishnabotna River that day, the oxen leading Peter Forsgren’s wagon tried to swim back to shore, and the wagon’s box came loose from its wheels. The men jumped into the river in order to fish out the wagon box along with its passenger. No one was severely injured, but two of the men were stepped on when they hitched the nervous oxen to the wagon again.

Two days later, on Saturday, June 25, they arrived at Council Bluffs Iowa, across the Missouri River from what is now Omaha, Nebraska, and they stayed there while gathering enough provisions to last for the rest of the journey. Council Bluffs was not only a stopping place for the Mormons, but also for people heading west to the gold fields of California. In six weeks, they had traveled about 265 miles.23

One journal states that on Tuesday, June 28, Neil Pedersen and his family left the company and would go no further.24 On Wednesday, June 29, another member of the company, Jorgen Nielsen, also said that he wished to remain in Council Bluffs, saying that there were liars and slanderers among the company and that he was no better among them than any other place in the world. John Forsgren declared that Jorgen Nielsen had slandered the church, and there was a unanimous vote that he be excommunicated from the church. Jorgen and his family left the following day. On Friday, July 1, Frederikke Frederiksen left the company and decided to remain in Council Bluffs. On Saturday, July 2, before the company moved to the shores of the Missouri River to continue their journey, Jorgen Nielsen returned to the camp with a Council Bluffs policeman, seeking his oxen that had been driven off by Hans Christian Hansen. The officer forced Hans Christian Hansen to return to the city, where he had to pay eleven dollars. On July 4, Hans Jorgensen and Dorthe Christensen were married in the camp.

On Tuesday, July 5, they began to ferry across the river during a thunderstorm, and four wagons got across. Some of the company members began building a bridge, and it took four days to get all of the wagons and oxen across. Four oxen had to be left behind for Jorgen Nielsen, who had sued John Forsgren for their return. On July 6, 1853, while the company was in the process of moving the wagons across the river, a daughter, Sarah Dianna Overlade, was born to Andreas and Karen Overlade.

On Sunday, July 10, the company was reorganized into new groups of fifty. On Monday, July 11, the son of Julius Herman Christensen fell off of the wagon, and the wheel of the wagon passed over his face. His nose was pushed into his face, and they had to remove a broken bone from his nose, but he survived.25 On Tuesday, July 12, John Forsgren had to return to Council Bluffs to pay thirty dollars in damages to resolve the lawsuit that had been brought by Jorgen Nielsen.

The first group of fifty commenced traveling on the morning of Tuesday, July 12, and the rest followed the next morning. On Friday, July 15, they reached the Elkhorn River. The ferry man at the Elkhorn Crossing allowed them to use his ferry at no charge. On the evening of Sunday, July 17, William Andersen fell, and his chest was run over by two wagon wheels, but he survived the accident.

They camped at Schell Creek on Monday, July 18. On Wednesday, July 20, the first group of fifty reached the Loup Fork of the Platte River, where they were once again ferried across at no charge. The Elkhorn Crossing and the Loup Fork were two of the most difficult crossings for pioneers heading west. The remainder of the company crossed the Loup Fork during the following two days.

As they got farther from civilization, there were not as many established places to camp. At times they camped at places that had no water or no firewood, so they were happy when they could find a camping spot that had both. Sometimes the trail would be sandy, causing them to move more slowly, so they were happy when they could have a solid road to travel.

On Sunday, July 24, after a slow trek across some high hills on a sandy road, they were able to camp by a small stream. That morning, Hans Andersen Peel died. Later that day, a son, Denmark Jensen, was born to Mads Christian and Maren Jensen. On Monday, July 25, they came to Wood River. There were no bridges or ferries, so they had to ford the river, which caused minor damage to some wagons.

They camped on Tuesday, July 26, by the Wood River, and on Wednesday, July 27, by the Platte River. When they camped near the rivers, they had plenty of water and firewood. As they traveled along the Platte for the next couple of weeks, some of the deeper streams that needed crossing had bridges that had been constructed by earlier Mormon companies, while others were shallow enough to ford. The streams they had to cross had descriptive names, including Elm Creek, Buffalo Creek, Six Spring Creek, Black Mud Creek, Bluff Creek, Petite Creek, Rattlesnake Creek, Wolf Creek, Watch Creek, Crab Creek, and Sand Hill Creek. They camped near Buffalo Creek on Saturday, July 30. On Sunday, July 31, John Forsgren informed the travelers that when they reached their destination they would not choose where to stay but would be appointed a place.

On Saturday, August 6, Christian Munk’s child fell off of the wagon, but was not injured.26 At their Sunday meeting on August 7, John Forsgren warned the people not to leave the camp without permission from their group’s captain, so that they could know where everyone was at all times. On Monday, August 8, Christian Christiansen died.27 On Wednesday, August 10, they were visited by a group of sixty Indians, begging for food, which the travelers gave to them. At their Sunday meeting on August 14, John Forsgren admonished the people to take care of themselves and not to try to take care of others.

On Saturday, August 20, they reached Fort Laramie, where they crossed the Platte River. By Monday, August 22, they were into the Rocky Mountains. Among the places they passed by and camped in along this leg of the journey were Little Spring Creek, Deer Creek, LaBonte River, Boyd Stream, La Prele Creek, Bad Slough, Sweet Water River, Devils Gate, Alkali Lake, Strawberry Creek, Pacific Creek, Little Sandy, Black’s Fork, and Ham’s Fork. On Thursday, August 25, Charlotte Thorp was run over by a wagon, but she survived the accident. On Sunday, August 28, Hans Larsen was married to Anne Marie Jorgensen.28 On Monday, August 29, Herman DePlade died. On Tuesday, September 13, Peter Madsen was mending a broken harness when one of his oxen got scared and dragged him for some time. He had to remain in the wagon for ten days before he could walk again.

On Tuesday, September 20, they arrived at Bridger’s Fort, where trail split. To the north, it became the Oregon Trail; to the west it became the Mormon Trail, heading toward the Salt Lake Valley. During this last leg of the trip, they passed Muddy Creek, Bear River, Echo Canyon, Cache Cave, East Canyon Creek, and Last Creek, until they finally arrived at Salt Lake City on Friday, September 30. Brigham Young directed the Danish immigrants to settle in what would later become Sanpete County, along the Sanpitch River.

============

Footnotes for “From Saint Louis to Sanpete County”:

20The journals from the journey simply say “The wife of C. Christiansen.” According to Conquerors of the West: Stalwart Mormon Pioneers, Vol. 1–2, edited by Florence C. Youngberg (Agreka Books, 1999), Christian Christiansen was the first Mormon convert in Denmark, and he married Christina Maria Hedvig Bruun in 1850. This book mentions their birth of stillborn twins near Keokuk.

21According to the LSD Church History web site, the child born on May 22, was Hannah Andersen, daughter of Wilhelm and Henrietta Andersen, but Hannah Andersen had actually been born on January 1, while the Forest Monarch was anchored in the River Mersey, so this couldn’t be her. The identity of this “Sister Andersen” remains a mystery.

22The information about Sugar Creek, as well as information about a few additional locations to come along the Mormon trail, comes from the LSD Church History web site. Although their information about individual company members seems to be inconsistent, their descriptions of locations along the trail seem to be reliable.

23After they left Council Bluffs, the dates do not always agree from one person’s journal to another. It is unclear whether some of the groups of fifty lagged behind the others by a couple of days, or whether the many months of travel had caused some of the journalists to lose track of what day it was. Most of the dates used in this story come from the company journal.

24It is difficult to find more information about this Niels Pedersen. The most likely candidate would be a Niels Pedersen whose gravestone in the Little Denmark Cemetery in Gowen, Michigan, says he was born in 1815 in Denmark and died in 1882. According to his memorial on Find-a-Grave, he had a wife named Katharine, which would make them match the Forest Monarch passenger list from New Orleans, which shows a Niels Peder Pedersen and his wife Catrine. There is also the possibility that the unnamed person who wrote this journal (or the transcriber) may have gotten the name wrong and actually been referring to Jorgen Neilsen, who left the company during the next couple of days.

25Herman Julius Christensen had three sons, Herman, Theodore, and Titus, but the journals do not clarify which son this happened to.

26Christian Munk had three children, Peter Mikkel, Petrine Christine, and Margrethe. The journals do not say which child this happened to.

27This family of Christiansens is a difficult one to keep straight. This Christian Christiansen appears to be the brother of the Christian Christiansen whose wife gave birth to stillborn twins in Keokuk. Their father was named Christian Christensen, and they also had a couple of brothers named Christen Christiansen.

28Although the company journal gives the bride’s name as Ane Marie Madsen, the Forest Monarch passenger list and all later records identify her as Anne Marie Jorgensen.

============

Childhood in Sanpete County

There is very little definitive information available about Peter Christensen’s early life in Utah.29 While most of the Danish Mormons settled in Sanpete County, the Forsgren family—John Erik, brother Peter Adolph, and sister Christine Erika—went to Brigham City, Box Elder County, and it is assumed that Peter lived there with them.30

John Forsgren and his second wife, Sarah Belle Davis, moved to Carson City, Nevada, in 1856, but it is not known whether Peter went with them or remained behind with other Forsgren family members. After they returned in 1858, John and Sarah separated and divorced. Sarah married a man named Joseph Clapper. John married a widow named Ingeborg Petersen, and they moved to Moroni, Sanpete County, taking Peter with them.31 At some point early in the 1860s, Peter left the Forsgrens and went to live with Abner Lowry, the son of John Lowry Sr.32 While he was living with the Lowry family, he was known as Pete Lowry.

During of the early decades of the Mormon settlement in Utah, there were ongoing skirmishes between the settlers and the Timponogos Indians. One of the leaders of the Timponogos was named Jake Arropeen. During an 1865 meeting to discuss the Indians’ claim that the settlers were responsible for the small-pox that had killed many of their people the previous winter, Jake Arropen became quite agitated. John Lowry Sr., who was working as an interpreter, pulled Arropeen off of his horse and was preparing to beat him when some bystanders were able to interfere and stop the fight. This incident is often credited for the escalation of the skirmishes with the Indians into what became known as the Black Hawk War. John Lowry later claimed that Arropeen was preparing to attack him when he pulled him off of his horse.33

Peter Christensen was too young to join the militia, but the Lowry men—John Sr., John Jr., and Abner (with whom Peter was living)—were all involved in this war against the Indians. Peter was appointed to stand guard over the cattle during this time. There is a story about Peter seeing some Indians coming toward the area while he was herding the cattle one day. He was on one side of a canal, and the cattle were on the other side. He could not swim, so he removed his clothes and tied them to a rock which he threw across the canal. Then he crawled across the canal while holding his breath, after which he put his clothes back on and herded the cattle back to the settlement.

When Peter left the Lowrys to go out on his own, he worked as a farmer and a freighter. In the 1870 U.S. Census, there is a nineteen-year-old Peter Christensen boarding with the Groosebeck family in Salt Lake City and working as a teamster. This could possibly be him, as no other Peter Christensen of that age can be found in Utah in that year’s census.

While looking through some belongings he had inherited from his parents, Peter found a Danish Bible. Inscribed in that Bible were the names Christian Christensen and Caroline Christensen. He believed these to be his parents, and even his death certificate lists his mother’s name as Caroline. He took the middle name of Christian in honor of his father, and for the rest of his life he was known as Peter Christian Christensen, later shortened to P.C. Christensen.

============

Footnotes for “Childhood in Sanpete County”:

29Most of the information about Peter’s life during this time comes from Quietly Going about Their Business, The Family Histories, compiled by Ida Belle Gledhill Christensen Buchanan, Peter’s daughter-in-law.

30Most of the information about the Forsgren family comes from Forsgren John Erik & Descendants, a web site created and maintained by the descendants of John Forsgren.

31The fact that Peter came to Moroni with the Forsgrens is assumed from a ten-year-old son named Peter being listed in the Forsgren household in the 1860 United States Federal Census. There is a possibility that this Peter might actually have been a son of Ingeborg, but nothing is really known about her life prior to her arrival in Utah the previous year. This particular census also showed the three children of John and Sarah Forsgren living with John and Ingeborg Forsgren, when they were actually living with Sarah and her new husband.

32Most histories state that Peter went to live with the Lowry family, without specifying whether it was John Lowry or one of his sons, John Jr. or Abner, but the History of Sanpete and Emery Counties, Utah, by W.H. Lever (Ogden, Utah, 1896) says that he lived with the family of Abner Lowry. This book states that Peter went to live with the Lowry family in 1858. Because there is a son named Peter in the Forsgren household in the 1860 Census and no Peter in any of the Lowry households in that census, it was probably in later years that Peter went to live with the Lowrys.

33This story comes from History of Indian Depredations in Utah, by Peter Gottfredson (Salt Lake City, 1919, Skelton Publishing Co.).

============

Still in Sanpete after All These Years

On January 29, 1892, Peter Christian Christensen married Mary Mallinson in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City. Mary had been born on July 21, 1853, in Ashton-on-Lyne, Lancashire County, England, to Edward Mallinson and Ophelia Turner Mallinson. She came to America with her parents in 1864 aboard the General McClellan. They had crossed the plains in the Joseph S. Rawlins Company, arriving in Salt Lake City on September 20, 1864. Peter and Mary set up housekeeping in Moroni, Utah, where Peter continued working as a farmer and a freighter.

Their first child, a son named Edward Christian Christensen, was born on February 2, 1873, in Moroni. Their second child, a son named Peter Angelo Christensen, was born on April 27, 1875, in Moroni. Perhaps to avoid confusion, he was referred to as Angelo, and it may be during this time that Peter Christian began to be known as P.C. Their third child, a daughter named Blanche Ophelia Christensen, was born June 17, 1878, in Moroni. Their fourth child, a son named Ernest Raymond Christensen, was born July 12, 1881, in Moroni. Their fifth child, a daughter named Hannah Caroline Christensen, was born November 11, 1883, in Moroni. She was always known as Daisy (Aunt Daisy to the nieces and nephews she doted on). Their sixth child, a son named Nelson Howard Christensen, was born March 23, 1887. He was known as Nils. Their seventh child, a daughter named Mary Viola Christensen, was born July 14, 1890, in Moroni. In her later life, when she supervised the kitchen at the George White Service Center in Portland, Oregon, during World War II, she was known as Shorty or Shrimp.34 Their eighth child, a son named Randall Christensen, also known as Ray, was born May 12, 1893, in Moroni. Their ninth and final child, a son named Frank Jay Christensen, was born October 20, 1859, In Moroni.

On April 11, 1882, Peter Christian Christensen proudly became a naturalized citizen of the United States. Having arrived at age three, he probably had no memory of any other home other than the country to which he was finally being accepted as an official member.35

During the 1880s, Peter ran a large general store in town. He sold much of his merchandise on credit, never turning anyone down if they needed supplies but were short of money. Because of this, he had a very low cash flow, and when he lost the store in the early 1890s his customers owed him thousands of dollars. Then he owned and ran a lumber mill. He had a fine team of horses that hauled the lumber by sleigh during the winter and by running gears in the summer. His daughters cooked at the mill, and they were there to care for him the day he cut his hand with a large saw. He never saw a doctor for this injury, and it left his two middle fingers stiff for the rest of his life.

Peter was active in local affairs. He served on the City Council, and was a delegate to many Republican Party conventions. In 1901, he was appointed Postmaster at Moroni. He remained in that position until 1915, when his son Randall was appointed to take his place. He continued to work there even after his son had taken over the reins.

Peter and Mary’s oldest child, Edward Christian Christensen, died tragically at the age of 29 on December 26, 1901. Ed had returned from a Christmas dance complaining of a suffocating feeling and died that night. His cause of death was listed as hemorrhage of the lungs.36

Their second son, Peter Angelo Christensen, was widowed on March 28, 1819, when his wife, Maren “Mary” Fechser Christensen, died during the influenza epidemic. Since Angelo worked in the coal mines and could not be at home to tend to his children, they all went to live with relatives. Most of the children moved in with aunts and uncles, but eleven-year-old Mary Berniece Christensen moved in with her grandparents, P.C. and Mary Christensen.37 She must have had a special place in their hearts for them to take on this responsibility at their advanced age. Five and a half years later, on October 1, 1924, Peter Angelo Christensen was killed when he was run over by a coal car at the mine where he worked.38

Peter Christian Christensen was a lover of music and had a large collection of records that he liked to listen to on Sunday evenings. He enjoyed dancing and was a favorite dance partner even among the younger ladies, and he also acted as caller for square dances. He enjoyed going to ball games and movies. During his later years, he wore a black skullcap to keep his bald head warm. He underwent cataract surgery, which was much more risky then than it is today, and the surgery took away a lot of his joy for life.

Peter’s wife, Mary, died on August 31, 1927, from an accidental injury after falling on some stairs.39

Their next-to-the-youngest child, Randall Christensen, died at a tragically young age on March 2, 1928, from pneumonia caused by inhaling fumes at his place of work, the Maytag Washing Machine Company.40 He was not quite thirty-five years old.

Peter Christian Christensen died on December 19, 1928. He left quite a legacy, survived by six children, nearly thirty grandchildren, and more than a hundred great grandchildren. The little orphan from Denmark left his mark on the world, and will always be remembered as one of the earliest settlers in Sanpete County.

============

Footnotes for “Still in Sanpete after All These Years”:

34This information about Mary Viola’s nicknames comes from an article in the Oregon Journal, August 17, 1945, section 2, page 2.

35Although his naturalization papers cannot be found, there are two separate mentions of the event in the Salt Lake Tribune, one giving the date as October 10, 1881, and the other giving the date as April 11, 1882. Since there is usually a waiting period between application and acceptance, the logical assumption would be that his application was accepted on October 10 and then finalized on April 11.

36This information comes from his obituary in the Ephraim Enterprise, December 26, 1901.

37This information comes from the personal journal of Theodore Angelo Christensen, the oldest child of Peter Angelo and Mary Fechser Christensen.

38This information comes from an article in the Salt Lake Telegram, October 3, 1924.

39This information comes from her death certificate issued by the State of Utah.

40This information comes from his death certificate issued by the State of Utah.

============